Are we doomed to the pain of attachment?

How can a human with a self ever attain abiding security?

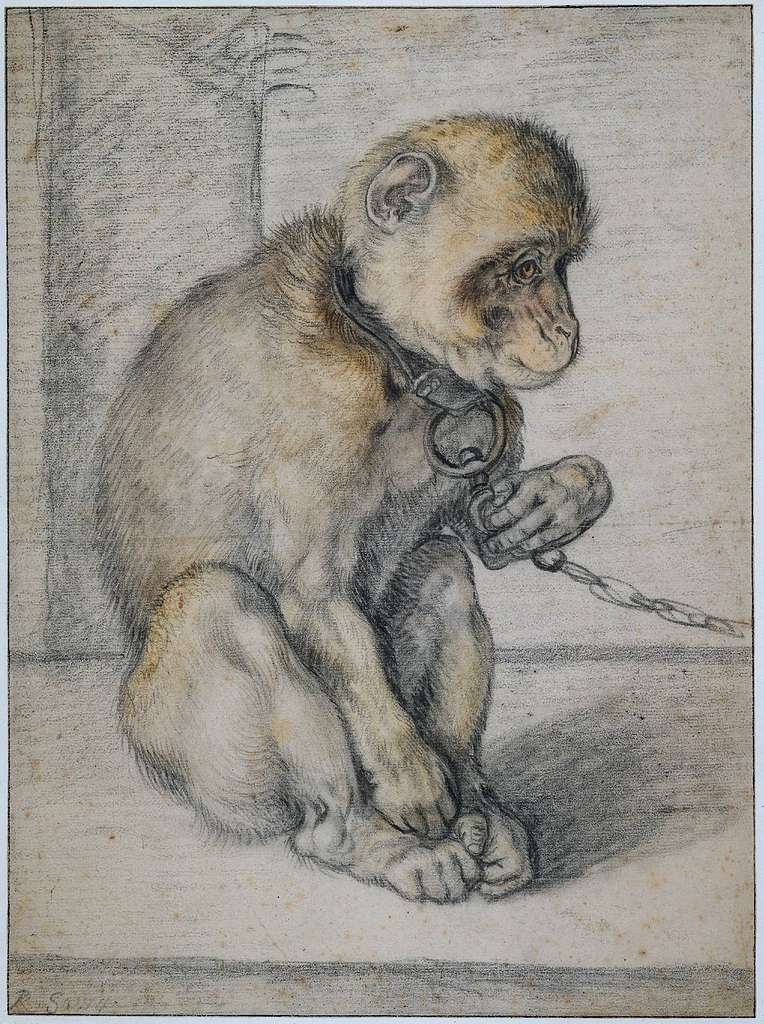

Last week I shared an explainer on Harry Harlow's experiments with baby monkeys, in which he explored the pivotal role that attachment to others plays in the psychological, physical, and social development of mammals.

This week's piece continues to interrogate that line of thought by asking about whether we are doomed to attachment and all of the pain that comes with it.

Human babies are helpless creatures, and this predicament pushes them into all sorts of strange situations.

Babies can hear people making regular patterns of sounds, but they can't form those sounds with their mouthes. They can see an object across the room, but they can't move themselves over to the object. They can know when they feel hungry or thirsty, but they have no ability to make these unpleasant sensations go away.

What marks the early human experience most acutely is helplessness, and it is this profound helplessness which engenders in the infant a corresponding reliance on their caretaker for even the most basic elements of life.

It's tempting to romanticize this state of affairs as the precious bond between mother and child, but we should also reverse this perspective in order to understand the terror and desperation which underlies this relation for the child.

My wife was lamenting in the car yesterday how many American women go back to work so soon after having children – "Babies don't automatically trust their mothers!" she said in exasperation.

The distinction is important. A baby craves the security, comfort, and nourishment only their mother can give, and thus they instinctively seek her out to receive those things from her, but we shouldn't confuse that for the child trusting that the mother will provide those things.

A child can sense that its mother has other priorities, and further, that she may not respond in a timely or effective manner to the child's needs. Trust must be built between a child and its mother, just as with any other human relationship.

I mentioned in last week's post about attachment that many parents today put their infants in another room at night, often leaving the child to cry themselves back to sleep. Folks practice this "crying it out" method under the illusion that their child will learn to "self-soothe," but the idea of self-soothing is a myth – the scared or hungry infant who goes back to sleep has simply given up in despair. They have accepted that their caretaker will not come to give them what they need.

Now, let us take the child's predicament one step further. Parents know that there are times when we physically can't give our kids what they need, but what about when we intentionally withhold things or even do them harm?

What parent has not lashed out at their child in the midst of sleep-deprived irritation? What parent has not forgotten to change their child's diapers for hours because they were engrossed with work? What parent has not declined to hold their child because they simply didn't feel like it in the moment?

And this is only considering parents who genuinely are trying to do a good job. There are many parents who do not even give the minimum amount of love and attention which a child deserves.

We can define the baby's predicament even more precisely now – their helplessness has compelled them to depend for their lives upon an other who is highly variable, complex, and fallible. More than this, the caretaker is capable of evil, the intentional and un-intentional harms which we perpetrate against one another on a daily basis.

All the instincts and chemicals in the child's body are forming an attachment to their caretakers in order to survive, but these caretakers happen to be other humans!

Pain is thus inevitable for every party involved, and there is no way to escape the trauma of being in relation with an other, especially one upon whom we are radically dependent.

And yet, is the infant's radical dependence on its caretaker not also a perfect picture of how we are forced to relate to others as well? In every encounter with other people, do we not find ourselves in an anxiety-inducing state of dependence?

Mammals in general, but human beings in particular, are highly social creatures. Perhaps only the insects have staked more than we have on the ability of the collective to overcome. We humans have developed highly complex systems of communication for coordinating our activities in order to acquire food, to mate, to care for our young, and to engage in all sorts of play.

But, as Harry Harlow's baby monkey experiments show, we are not simply looking to acquire the minimal resources of existence through these relationships of dependence on others. At a certain point, connection itself became an end in itself, and one which we have elevated to the place of the highest good and ultimate end.

The baby monkey's intense bond with the cloth mother which provides comfort and security vastly supersedes the baby's relationship with the wire mother which merely provides it with the sustenance it requires to go on living. Harlow even demonstrated that the baby monkey would not approach the wire mother when it found itself in a strange and unfamiliar environment!

Near the end of this invaluable dialogue held between J. Krishnamurti and a few scientists in Ojai near the end of his life, Krishnamurti makes a crucial claim about attachment – there can be no hope of peace without every human achieving such a sense of security that all misery and violence can cease.

To this point in the conversation, Krishnamurti has been patiently building his case that the source of all misery is the self and our attachment to it. He distinguishes the suffering which we witness in nature (which he sees as inevitable) from the misery which we experience as humans, which seems to derive from our self-consciousness perception of ourselves as separate from other beings. This experience of ourselves as both separate and dependent creates an intense craving for security, a drive which leads to the full range of human dysfunction.

But, Krishnamurti seems to ask with genuine curiosity, is there a deep abiding security which goes beyond our idea of security? If security is the most fundamental drive, the problem to solve above all is the question of security.

"The self can never have that security, because he is in himself divisible,” says Krishnamurti. How can a human with a self ever attain abiding security?

After bringing up the power of the instinctual patterns we inherit from our ancestors, a scientist wonders to Krishnamurti: "“Are we too conditioned to be free?”

He replies, “That’s what I want to discuss — whether it’s possible to change the human condition. To not accept it.”

Let us discuss precisely this question – whether it's possible to change the human condition. To not accept it. It seems to me that God did not accept our condition, and that for that reason at least, we ought not to either. Herein begins the journey.

Thanks for reading this week's piece at Samsara Diagnostics! Keep your eyes out for next Friday's review of Slavoj Žižek's newest book Freedom: A Disease without Cure. It's an engaging read thus far – Žižek is at his best tackling tough questions in unexpected ways, and also doing close readings of other thinkers. I'm excited to share my thoughts with you about this text soon!