The father is a screen - responding to Girard's critique of the Oedipal complex

This piece continues our ongoing series on the philosophical problem posed by the emergence of self-destructive behaviors in human beings, and it builds on a prior essay about how Lacan draws out the under-theorized role of fantasy in Girard's theory of desire. This piece expands our understanding of a Lacanian theory of desire built on a lack which pushes.

Girard's mimesis as a screen

Both Girard and Lacan present what I have called “push” theories of desire in which the nature of lack plays the primary role in the genesis of desire, and the qualities of the desired object play a secondary and complementary function.

However, if we compare Girard's mimetic theory to Lacanian psychoanalysis, we find that Lacan supplies the psychological mechanics which Girard leaves underdeveloped in his account of desire as imitation of a model. In fact, we may even find that Girard's account obscures what is really going on.

Žižek interprets Lacan’s cryptic phrase “there is no sexual relationship” to mean that there is no universal formula for what or how to desire.

Since a formula describes a durable relation between two or more terms, Lacan's claim is that, in the case of the human being as a lover in their world, nature does not supply a method which allows us to reliably determine what a given human will or must desire.

In this way, Zizek simply re-states the problem we have been discussing thus far — there is no naturally desirable object, but only an interpretation of how the subject and object should relate.

Each individual must rely on a private hermeneutic which they have cobbled together over time through the observation of and identification with various models through fantasy.

Girard’s mimetic theory attempts to solve this lack of universal formula by spinning a story about a model who teaches us how to desire, erecting what Zizek refers to as (in a twist on a Lacanian notion) "the subject supposed to believe."

Just as the doubting Christian can take solace in Jesus believing for the both of them, so too Girard's mimetic subject can tell themselves the story that desire originated in the other who taught them how to desire, thus allowing them to continue believing that desire has some basis in the external world rather than in their lack (and the Other's lack).

Even Girard's notion of myths as post hoc justifications for the collective murder of a scapegoat still presumes a subject or community of subjects who truly believe the myth. This hypothetical group of individuals who sincerely believe provide the imaginative support for us to believe as well.

In positing the existence of this subject-supposed-to-believe, the Girardian subject can still manage to halt the slippage whereby the truth of each subject's desire infinitely regresses into a groundless oblivion.

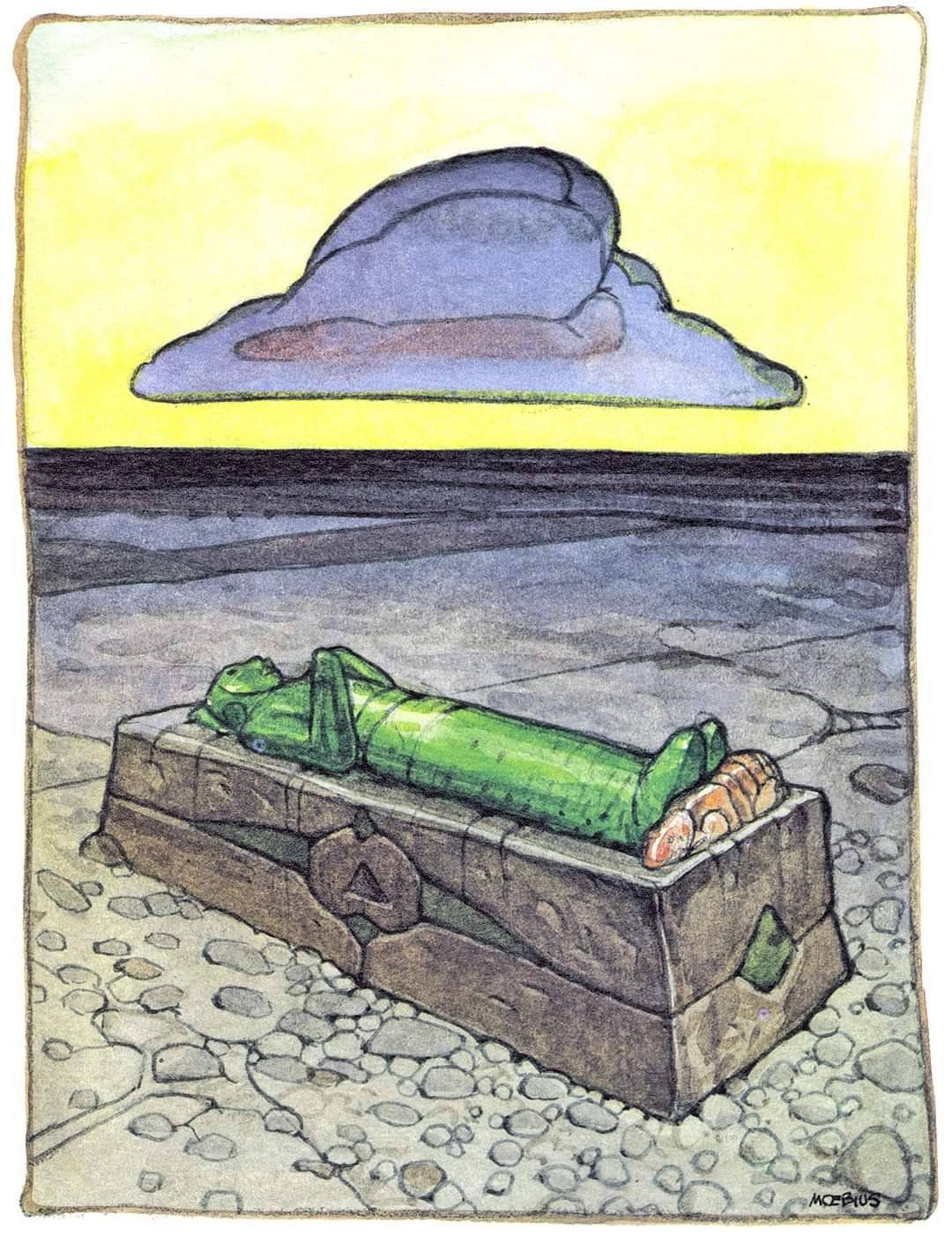

Girard thus shields the reader from grim inferences concerning the dire situation of the subject and the lack in the Other. In fact, we might fruitfully read Girard's "mimetic vignette" as a phantasmic screen against this confrontation with the contingent abyss of desire.

Rebutting Girard's critique of the Oedipal Complex

We can even observe this screening function operating in Girard's critique of Freud's myth of the Oedipal complex.

Girard intends his critique as a moment of radical truth telling which unmasks the myth of the founding murder (sacrifice) of the ur-father which Freud positions at the heart of civilization.

However, the mimetic myth he employs in its stead speaks to where Girard’s own theories stop short of the traumatic encounter with desire’s origin in lack.

Girard complains concerning the Oedipal complex that it gets the rivalry between the father and the son precisely backwards — the father sees the son as his rival first, and only later does the son come to realize that he has become his father's rival.

Rather than desire for the mother being the original spark for the conflict in the Oedipal triangle, the true catalyst emerges from the son's attempts to imitate the father's desire, which comes inevitably to rest upon the mother.

The child thus desires the mother by way of imitating the father, and thereby inadvertently enters into a rivalrous relationship fraught with all the antinomies we have discussed thus far.

In Girard's interpretation, the father is the aggressor and the child becomes an unwitting victim of his father's jealousy.

This Girardian interpretation of the Oedipal complex misses the primacy of the child's relationship with the mother from its earliest moments (this is where the psychoanalytic grounding in clinical observation reveals its value).

The child's first relationship is to the mother, even recognizing her voice from within the womb. The child's sense of self only emerges subsequently from the experience of being apart from the mother.

In her arms, the warmth and euphoria of feeding at her breast assuages all the child's fears and chaotic drives, sheltering it from the harsh world of being a lacking being. The child and the breast are one, and only in their separation does the child experience the terror of their own body which produces unpleasant sensations, spasms, and emissions totally outside of their control.

From the child's perspective, the relation to mother precedes and grounds individuality itself, even making this individuality a negative thing in so far as it entails being cast out of total immersion in bliss.

This relationship does not require the meditation of the father figure, and while the father is clearly preeminent chronologically, it is the father who appears here to the child as the interloper!

This is not to ignore that even from the earliest moments this child-mother unity is always unstable.

The child will inevitably begin to pick up on the subtle hints that all is not as it seems in paradise. Why does mother not immediately quash any rising displeasure in the child? Why does she sometimes seem distant or distracted? Why does she leave and come back? Why does she not come back right away?

The child cannot help but notice the mother's desire may be oriented beyond it as she searches for something which she lacks.

Once the child can discern that Father has what Mother wants, the child is caught in a bind. They simultaneously desire what mother desires, that is, Father, but they also wish to destroy Father to obtain whatever Mother desires in him. I want daddy to love me, but I also want mommy all to myself.

The child can be tempted to reconcile these conflicting desires through the fantasy of re-constituting their lost unity by returning to union with the mother through becoming the object which the mother desires, that is, what the child perceives they lack.

However, this solutions possesses some terrifying accompaniments which can portend the ultimate obliteration of the child’s individuality into the total Oneness of the mOther-child unity.

[We will explore these movements of the subject in a future essay where we attempt to speak more concretely about how behaviors of self-harm arise from the accompanying vacillations.]

In closing though, let us clearly re-iterate that the fantasy of unity with the mother through becoming the object of her desire serves as a screen for the impossibility of acquiring the desired object.

At the heart of the Oedipal complex there functions a fantasy which says that the reason the boy cannot have his mother is because his father stands in the way, but this story simply obscures the true nature of the situation — that what the boy desires is something his mother could never give him, and conversely, that what his mother desires is something he could never be for her.

In his mimetic story, Girard mistakenly believes the child's fantasy, and thus becomes unable to lead himself or his readers all the way to the end.

To proceed to the next essay in the series, click here. Thanks for reading!