How will our tears water the earth?

How shall we water the earth with our tears of joy? I ask myself this question in consternation as I wrestle with the Christian vision of the new heavens and the new earth in which suffering has no place.

"Water the earth with the tears of your joy and love those tears."

In The Brothers Karamazov, the words of Father Zosima echo in Alyosha's mind as he abandons Zosima's funeral in a moment of ecstatic realization --

Alyosha stood, gazed, and suddenly threw himself down on the earth. He did not know why he embraced it. He could not have told why he longed so irresistibly to kiss it, to kiss it all. But he kissed it, weeping, sobbing and watering it with his tears and vowed passionately to love it, to love it for ever and ever.

How shall we water the earth with our tears of joy? I ask myself this question in consternation as I wrestle with the Christian vision of the new heavens and the new earth in which suffering has no place.

The promised hope outlined in Christian Scripture culminates in the final renovation of the world – God dwells with humanity, swords are beaten into ploughshares, and the lion lies down in peace with the lamb.

But, in a world without suffering, how will we experience joy? How can there be overcoming without suffering? What should we make of such a promised life in which negation is absent?

When God wipes away every tear, how will we water the earth with our tears of joy?

My encounter with Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche first awakened these questions in me.

With his insistence on the inextricable relationship between struggle and joy, he painted a picture for me of a higher form of life which loves the world – which would weep tears of pure joy instead of seeing existence as a prison to be escaped or destroyed.

A lively creature does not seek total relaxation or the cessation of tension, but rather a greater intensification of the sense of its own life. The aim of life is not rest but a struggle, and we pervert life into a quest for death when we elevate the extinguishment of suffering to the highest ideal.

As I read Nietzsche's writings for the first time in the spring of my senior year of college, they were a revelation to me. He was so much more than I could have imagined. His words challenged me, provoked me, comprehended me, baffled me, at times terrified me, and frequently inspired me.

With his words, Nietzsche had reached me from across time, and was breathing life into me simply through the sheer force of his own life – like a star burning itself out brilliantly.

Nietzsche's hardness, first with himself, and then only secondarily with others, was like a blast of cold mountain wind, bringing with it a frigid doubt and bone-chilling questions that I felt in my innermost parts. They demanded that I rise to the challenge, and I knew that I could not flee from them without regretting it my entire life.

Sometimes I struggle to communicate to others why I felt these questions to be the problems that I felt that they were, but I cannot help feeling radically implicated in Nietzsche's venomous words about Christianity's world-hating tendencies and its devaluation of strength and beauty. These accusations seemed then and remain for me today of paramount importance.

Laying it down to take it up again

Nietzsche's wrestling with life, beauty, hatred, and suffering cast my life into doubt – the most fruitful doubt I've ever experienced.

His work calls into question Darwin's hypothesis that life's basic drive is to reproduce. Instead, Nietzsche claims, life moves forward by continually putting itself at risk. This is what he means by his phrase 'will to power' – life's drive to constantly overcome itself through testing its limits. This sense of an ascending life which overcomes its limits is the high a vital creature is always chasing.

When we risk something, we lay it on the line in order to gain something greater, or perhaps to receive our original sacrifice back tenfold. The efficacy of the risk lies in the possibility of an abundant return, and the greatest rewards tend to come from those risks where the possibility of loss is also the highest.

But, how does one risk in the new heavens and the new earth of Christian Scripture?

In a world where pain and death are no more, what happens to the transformative moment of a child falling down but choosing to get back up again? What about the majestic strength of the one who runs directly towards danger for the sake of an other? What about those exhilarating activities in which we stretch ourselves to our absolute limit, risking failure, but seeking to extend our own limits through the act of testing them?

How can we risk in a foam-padded world with no tears, no pain, no death?

This is how the Christian eschatological vision appears to me, and I cannot comprehend it. Don't the most beautiful things come when we lay something precious down in order to take up something of greater worth?

Does the Christian eschatological vision entail that when we climb a mountain in the new heavens and earth that we will not get short of breath, experience acute hunger, expose ourselves to danger, or feel that burning in our legs which tells us we are about to make a break through? If not, how can we experience the true joy for which we were made?

Nietzsche hates Christianity precisely because it teaches people that the culmination of the world is its destruction and renewal in which suffering will be entirely done away with. While Jesus promises that his followers will suffer in this life, they only endure that suffering under the belief that they will enter into an eternal bliss when he returns. Christianity has at its core the conviction that suffering is an injustice, and that it therefore must be done away with.

The Wedding and the Orgy

In the book of Revelation, St. John receives a mystical vision of the end of the world as he languishes in exile on the island of Patmos. This vision shows him the culminating moments of history in which God renews creation through the arrival of His kingdom. The heavenly city descends to earth, and God's union with His people is inaugurated by a wedding.

In this wedding, the Son of God takes the Church to be his bride, and eternity is ushered into time under the aegis of the sexual union of the wedding night and the perpetual feasting which follows such a glorious wedding.

While Christian eschatology presents us with the world's culmination in a wedding, Nietzsche seems to oppose to this image that of the Dionysian orgy. A pure instantiation of the chaotic forces of nature – the flailing of limbs, raw sexual energy, impassioned cries, blind fury, and deep drunkenness. Near the end of his life, Nietzsche scrawls his defiance as 'Dionysius versus the Crucified.' He sets the god of wine and ritual ecstasy against the humiliated and crucified God.

This dialectic of weddings and orgies brings us back to Alyosha's mystical experience – When Alyosha falls down on the ground, kissing the earth and blessing it with his tears, the image which has driven to this point was also a wedding – the Wedding at Cana.

In Scripture, not only does history end with a wedding, but it also begins with a wedding. The Genesis account present us with the creation and union of Adam and Eve, and the Gospel of John recounts how Jesus Christ's ministry as the Second Adam also began at a wedding where he turned water into wine. This was his first public miracle.

Alyosha sees in a vision Father Zosima enjoying the wedding at Cana, saying --

Do not fear Him. He is terrible in His greatness, awful in His sublimity, but infinitely merciful. He has made Himself like unto us from love and rejoices with us. He is changing the water into wine that the gladness of the guests may not be cut short. He is expecting new guests, He is calling new ones unceasingly for ever and ever...

I ask these questions about how to envision the culmination of all things precisely because I believe that they can be answered, although only with great labor.

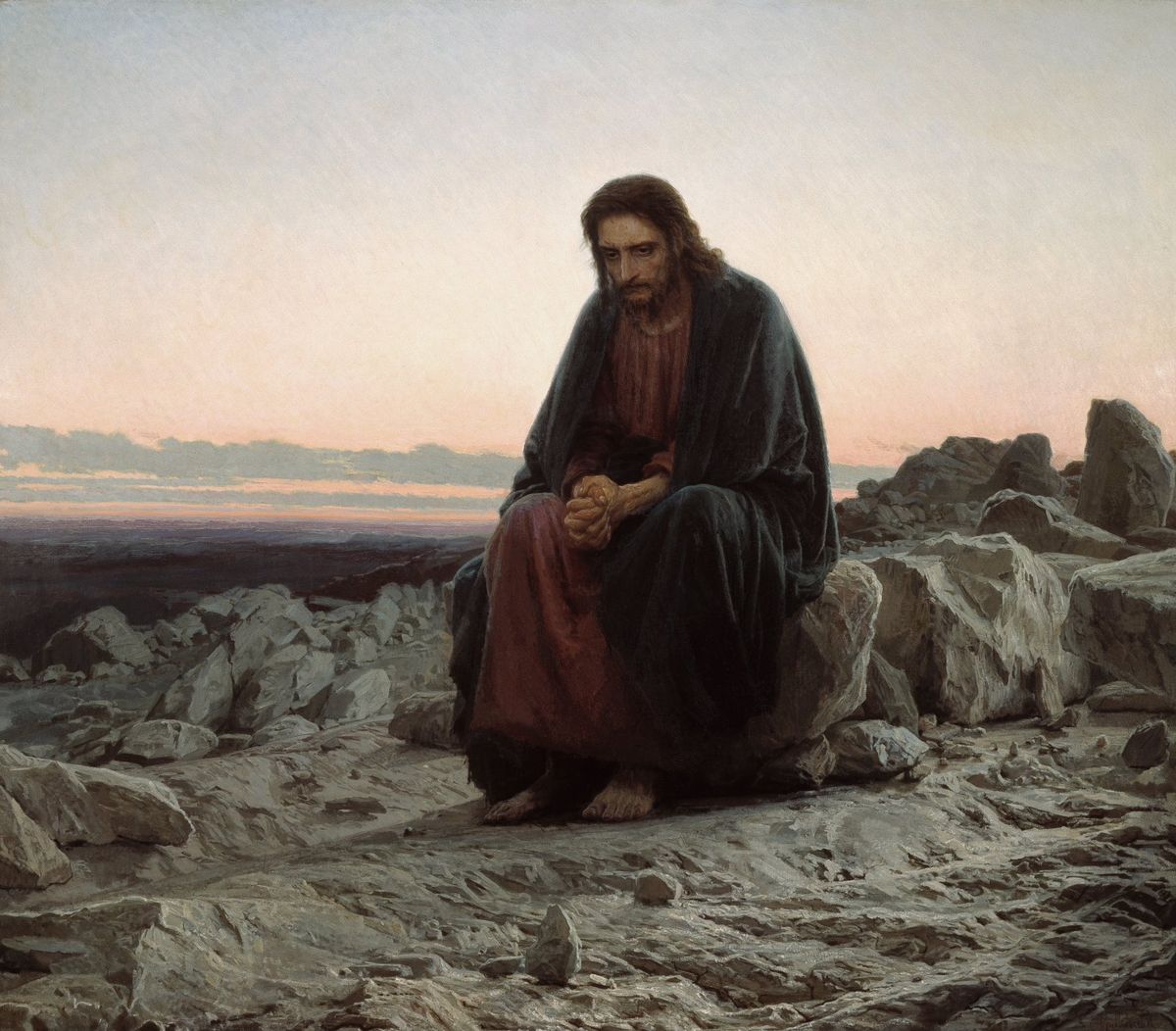

The one who turns water into wine was the same one who turned death into life, but not by way of a pure negation – the work of God's love in His creation is a transfiguration, a translation and intensification of its peculiar glory.

This image of the wedding where the Galilean robs Dionysius of his authority, and goes on to pursue his beloved even unto death, elevating the whole of history to nothing but the revelry of a wedding between God and His beloved...

How can we respond to such a marvelous thing? We press on with joy and ardor, carrying only a flask of wine to sustain us in this wilderness. God has begun to water it with His tears. May we join Him, and one day up will grow a garden.

I read The Brothers Karamazov during spring of my freshman year, and I see now that it was completely wasted on me. I hardly scratched the surface of what Dostoevsky was wrestling with through his characters. However, this scene of Alyosha weeping was one of the few things which stuck with me. I have had the growing sense that I need to return to fiction to re-read the books which I read in my youthful hubris without comprehension.