Oedipus in a Biopolitical World (Part 1)

Foucault’s critique raises the question of how a psychoanalytic theory which is based on the notion of repression can speak to a society which everywhere commands the liberation of desire.

Speaking about our desires no longer offers the liberation which it once seemed to. Such speech today feels like exposing ourselves in front of a faceless audience, and our compulsive confessions serve only to make us the objects of violent mockery, fetishistic enjoyment, or sociological analysis.

Michel Foucault was one of the earliest theorists of the acute dangers of this newly emergent “compulsion to speak." Foucault was also a critic of psychoanalysis, and rejected it precisely because he believed it was complicit with this new experience of power’s command to speak about our desires. The psychotherapist’s office had become the secular confessional booth.

Foucault’s critique raises the question of how a psychoanalytic theory which is based on the notion of repression can speak to a society which everywhere commands the liberation of desire. How does it avoid becoming either completely irrelevant or deeply complicit with power’s operation to shape us as subjects?

In short – what place can Oedipus find in our world today?

The myth of liberation through speech

The Repressive Hypothesis

At the outset of the first volume of his History of Sexuality, Foucault tells us that his historical and theoretical project aims to call into question a cultural myth which we tell ourselves about sexuality. He calls it “the repressive hypothesis.”

This repressive hypothesis contends that, while sex was spoken of frankly and without dissimulation as early the seventeenth century, the Victorians imposed a regime of strict prohibitions on sexual behavior, stigmatizing these "natural" sexual urges through an excessive silence, and heaping shame upon anyone who transgressed this unspoken order. Expositors of this repressive hypothesis consequently exhort us to break the silence of the Victorians, and to liberate ourselves from these prohibitions in order to live happier, healthier, and more enjoyable lives. [1]

As a gay man, Foucault certainly has a personal interest in the decline of traditional Christian sexual prohibitions, but he’s wary of trading a cruder form of slavery for a more sophisticated one. In particular, he’s interested in how advocates for sexual liberation seem to perpetuate a relentless pressure to talk about sex. More so than ever before, in fact.

The advocates of the repressive hypothesis claim that through bringing sex into the light of language we can free ourselves from the guilt and shame which has traditionally surrounded it. [2] “Be liberated through speech!” they cry.

But, Foucault asks, if speech leads to liberation, why has our society's ever-expanding torrent of words about sex not achieved the promised emancipation from the repression of traditional sexual mores? [3] Is speech really the path to liberation which its proponents claim it is?

Foucault wonders how Westerners can seriously claim that we are a sexually repressed society when we have produced more spoken, written, and visual material about sex than any other society in human history. [4] Our scientists research sex. We write books about sex, produce an endless stream of pornography, shoot sexy movies and TV shows, and even teach “sexual education” in our schools.

Is repression actually what’s happening here, or is something else more complex afoot? [5]

Confession and the production of Truth

Where one thing is repressed by power, another adjacent behavior is encouraged, even demanded. Foucault thinks that we can discover a clue to this operation of power by noticing how the myth about repression paradoxically produces so much speech about the very thing it claims is repressed.

When we look a little closer, we realize that repression and demand often coincide at a crucial juncture – we are commanded to speak about the illicit thing, and to be made free of it by bringing it into the open. [6]

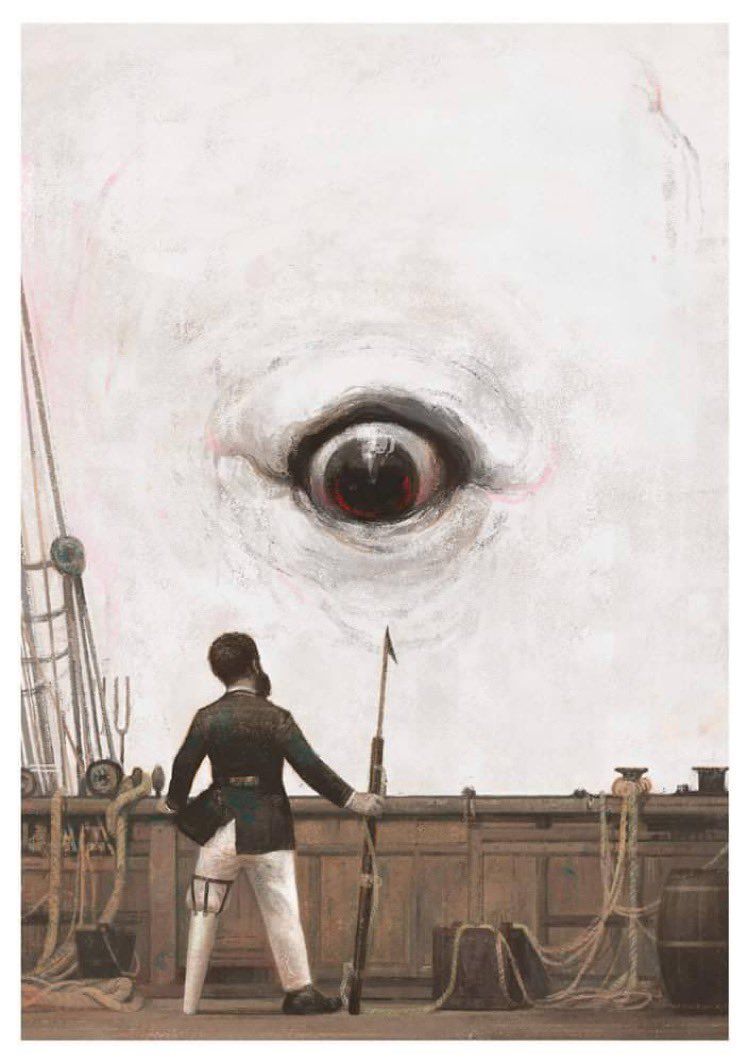

Thus, a danger lurks in the sexual libertine’s cry to bring sex into the light – Who does he take to be his witness? To whom does he lay himself bare? And what does his act of confession achieve?

“We have since become a singularly confessing society,” [7] Foucault says, identifying the act of confession as the most primordial form of the promise of liberation through speech. [8]

The act of confession differs from merely speaking the truth in one's heart because it requires a someone to whom the confession is addressed. One who confesses speaks to be heard by another, and the confessor seeks absolution from an authority who can give it.

This promised liberation through discourse is a promise which power makes to the subject, and thus to comply with the demand to liberate repressed desires through speech serves ultimately to perpetuate the interests of the particular biopolitical regime in which we find ourselves entangled today [9].

[Please note that in part two of this series, we will define "biopower" and "biopolitics" by looking at Foucault's analysis of our society's transition from "the right over death" to "the right to life."]

For this piece's purposes, I would draw your attention particularly to how the operation of power in this instance is oriented towards "producing the truth," that is, excavating the inner secrets of the human heart.

The apparatus of power hunts after usable information which it can put to work towards optimizing all of human life – including our inner world.

Power encourages us to produce the "truth of the matter" about our inner life by performing a two-fold maneuver, the contours of which we have already begun to outline --

First, the story about repression creates the impression that a truth about ourselves is hidden in our depths. Thus, the prohibition itself causes a secret to crystalize into an object deep within us.

Then, second, power must extract this newly formed truth through an enticement to speak. We must be encouraged to perform an archaeology on ourselves in hopes of uncovering this repressed secret truth within us. This happens through speech.

Ultimately, this speech brings the truth into a medium which power can understand and manipulate – data. The information of our society's constant speech produces a data set which can be recorded, analyzed, and acted up later.

Turning towards the second part

Foucault wants his readers to see that the complex power dynamics of the confession describe the operation of sexuality in the West far more accurately than the popular notion of sexuality as repressed.

In this way, he reveals that the myth about repression serves an ideological function to dupe us into giving power what it wants. We believe we are repressed, and the very acts we believe will liberate us ensnare us more fully in power's grip.

Foucault identifies psychoanalysis as a secular form of confession in which one works on one's self, for in psychotherapy just as in confession one becomes both the speaker and the object spoken about. One applies probing questions, a watchful eye, and a searching demand, and all this takes place in the presence of the therapist.

This figure of the therapist, sanctioned by the government and representing scientific expertise, acts as the witness who observes the subject's labor of speaking, registers the words' receipt with power, verifies the efforts of the confessor, passes judgment regarding the labor's truth or sincerity, and renders absolution through the form of diagnosis and treatment. [10]

What Foucault has described here seems to me to be a scathing critique of our culture's obsession with therapy and the use of medicalized concepts for understanding ourselves and our suffering.

However, I'm also of the belief that psychoanalysis can avoid Foucault's critique, and even point us in a contrary direction to our biopolitical society. Psychoanalysis can help us escape the worship of the seemingly contradictory idols of our time – infinite victimization and infinite optimization.

How can psychoanalysis avoid the complicity with power which Foucault describes so masterfully? Before we can answer this, we have to clarify Foucault's theory of "bio-power," and why the techniques of power to "produce the truth" through confession are a unique product of the particular sort of society we live in today.

We will turn to that task in next week's installment of this series.

Notes

- Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Vintage Books, 1990), 3-5.

- Ibid., 8-9.

- Ibid., 12, 131.

- Ibid., 32-33.

- “The way in which sexuality in the nineteenth century was both repressed but also put in light, underlined, analyzed through techniques like psychology and psychiatry shows very well that it was not simply a question of repression. It was much more a change in the economics of sexual behavior in our society.” Michel Foucault, Ethics, ed. Paul Rabinow (New York: The New Press, 1994), 126.

- Foucault, History of Sexuality Vol 1, 60, 69.

- Ibid., 59.

- “Not only will you confess to acts contravening the law, but you will seek to transform your desire, your every desire, into discourse.” Foucault, History of Sexuality Vol 1, 21.

- Ibid., 62.

- Ibid., 61-62.