The face of God in the face of my neighbor

Towards a Protestant Mysticism

Although I think that Protestants have much to offer the practice of Christian mysticism, we have tended to look to other ecclesial traditions when broaching the question of mystical experiences.

My sense is that we have internalized the impression that we are the illegitimate step-child of the Christian mystical tradition, and because of this we feel the need to pass off our own thoughts as the thoughts of others.

For this reason too we have rarely asked in what a truly Protestant mysticism might consist (although, I think that the Puritans present a notable exception which deserves further study).

By and large, the Protestant traditions tracing their roots to the Magisterial Reformation — Lutherans, Calvinists, Anglicans — have failed to articulate a robustly Protestant conception of spirituality. In America, at least, we have left this spiritual work to our Anabaptist brothers and sisters, with disastrous consequences for the Church and for society.

It was the abdication of our mystical labor which left the space open for the forms of spiritual experience which were eventually co-opted by the American market economy to form pliable and dis-engaged capitalist subjects. But this is a story for another time…

Allow me to briefly propose two characteristics which I believe mark a Protestant mysticism which flows from the tradition of Luther and Calvin — (1) mediation and (2) action.

(1) A Mysticism of Mediation

At the heart of Christian mysticism stands the Beatific Vision — the awful blessing of the direct vision of God. Be it pure contemplation or ineffable appearance, the mystic strives for this full union with God in which nothing remains veiled as God gives Himself fully in Love.

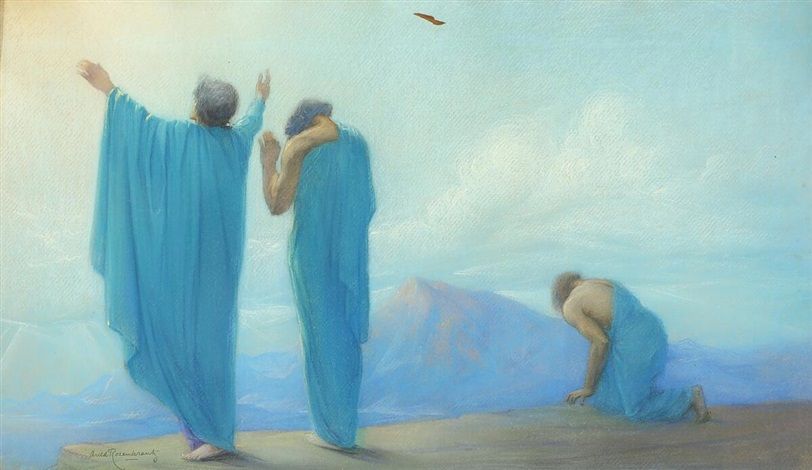

However, a Protestant mystic does not seek the beatific vision directly, but instead they search for the face of God in the visage of their neighbor. They do not recede in a movement of withdrawal, but rather as they immerse themselves in God’s world, busying themselves with love and service, their reality becomes transfigured rather than transported.

In light of the astonishing event in which God has become a human in the person Jesus of Nazareth, God has made His encounter with us inseparable from our confrontation with a human face. God’s presence is now inexorably mediated through the other. He has made it such that we can seek Him no other way than through wounded hands and bloody face.

Protestantism then fully accepts this new logic of mediation, whereby God gives Himself to us through His creation, which is another way of saying that God meets us precisely where we are at, but in so doing transforms the locus of meeting. God’s journey in creation from God to God-with-us entails a movement of mediation in which both terms are transformed for having traversed the dialectical process. This new unity is a dynamic synthesis, not an immobile or static state.

In Matthew 25, Christ tells a story of believers at judgment day who are welcomed into the kingdom of Heaven, but these faithful ones are confused, explaining that they have never seen Christ in the flesh until this very moment. In revealing to these confused saints how they had indeed served him, Jesus confronts us with a shocking claim — “Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me.’”

Whether it be sharing a cup of cold water or giving away all our earthly possessions, Christ says that in giving generously to the one in need we render the same act of mercy to him. Such is the severity with which Christ has bound himself to the face of the other that in loving our neighbor God takes us to have loved Him personally as well. This is the God who has made Himself manifest through his creation, in the face of the other.

(2) A Mysticism of Action

With the movement of mediation at its heart, Protestantism now presents itself to us as a mysticism of action, not of contemplation.

When faith receives the completed work of Christ in a humble poverty of spirit, the work of faith releases the believer back into the world to love and serve. These are the works of faith, the fruits of the Spirit at work in us, which means that the works themselves are the means by which we experience the full presence of God in Christ by the Spirit.

Contrary to the Roman Catholic critique that justification by faith alone demotivates good works, the Protestant understands that our union with Christ through faith is precisely what opens up the space to live a life of service to God and neighbor, and that only by faith can we receive that Spirit which transfigures our actions and our world.

This transition from faith to the works of faith mirrors Martin Luther’s description of the Christian life in the The Freedom of the Christian, a foundational text for any future development of a Protestant mysticism.

In his brief tract, Luther describes the two paradoxical states which define the Christian life, and whose dialectical relation serve as the engine of the Protestant mystic —

- The Christian is lord of all, completely free of everything.

- The Christian is servant of all, completely attentive to the needs of all.

Luther’s formula that “the Christian is lord of all, completely free of everything” proceeds from his understanding that faith fulfills the whole of the Law, both in despairing of its ability to keep the Law and in fully receiving the complete obedience which Christ rendered on our behalf. This total victory and renewal which proceeds from the faith given by God is experienced by “inner person,” according to Luther, and thus through faith the inner person comes to enjoy all the benefits which proceed from loving communion with God.

In the second half of the tract he turns to contrast the inner person with the outer person, for the inner person having become completely free of the need to earn God’s love, the outer person is now freed to immerse themselves in the world to love and serve their neighbor.

The outer person has become a “servant of all” who can be completely attentive to the needs of others because they no longer need to be concerned for their own needs — they have received all the glorious riches of God Himself, and having been filled up, they wish now to pour themselves out.

This immense generosity of Spirit proceeds directly from the way in which the inner person has been set free from every sort of bondage.

Turn towards your neighbor

In closing, we may consider how Jesus answers the Pharisee who asks for the greatest commandment in the Law — “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, mind, and strength, and the second is like it; you shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two hang all the law and the prophets.”

Why did Jesus answer with two commandments when the Pharisee asked only for the greatest commandment? The paradoxical reading is the simplest — they are the same commandment.

Let this be the guiding light of the Protestant mystic then — to turn towards our neighbor with love is the sum total of Christ’s command, for in loving our neighbor we have loved God Himself.

May God give us the grace to do so. Amen.