The plasticity of human desire

Humans are the most un-natural of all the animals. We might frame this observation in terms of the contrast which psychoanalysis draws between instincts and drives.

Have you ever had the pleasure of enjoying something simply for its own sake?

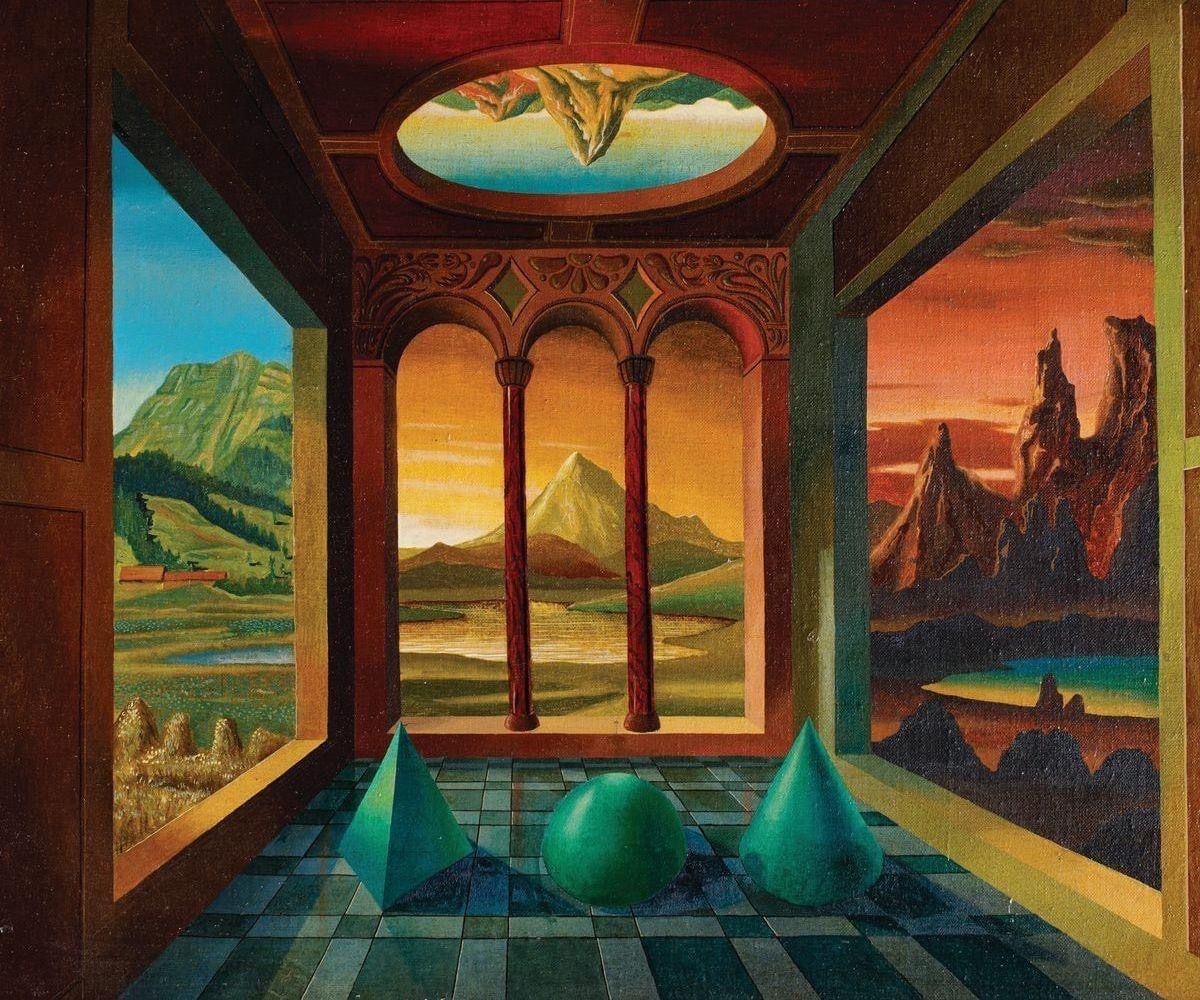

Perhaps the most enjoyable things in life are those which serve no purpose other than themselves. Something can become distinctly enjoyable when it is not subordinated to any higher purpose or overriding utility.

Removed from the mundane economy of ends, these wasteful acts become sacred. By a ritual of setting apart – making holy – such things can be elevated to a new spiritual significance, renewing both ourselves and them in the process.

This ability to abstract objects from nature's kingdom of ends, while not the exclusive domain of humans, seems to be more foundational for our nature than for any other creature on God's green earth.

We humans are the most un-natural of all the animals.

We might frame this observation in terms of the contrast which psychoanalysis draws between instincts and drives.

Animals have instincts – where to seek food, where to find a mate, where and when to migrate, and so on. These instincts are biological urges which tightly correlate to some action or object which would satisfy the instinct. The animal feels hungry, so it eats and is satiated. The animal experiences an overpowering need to copulate, so it finds a mate.

Instincts supply a biological signal and energetic motivation to lead an animal towards a utilitarian end. Then, having done its job, the instinct disappears.

Psychoanalysis gets criticized in Christian circles for reducing human beings to animals, but the story is actually more complicated than that. Freud's theory does not propose that human beings have these natural instincts which society suppresses, and that we would all be happier if we just more openly and unashamedly allowed ourselves and each other to satisfy these instinctual needs. This explanation misses a crucial move that psychoanalysis makes in its description of human beings and their drives.

For Freud, the drives which human beings experience are instincts which have become de-coupled from their natural object. As such, the drives now operate within humans as these sources of free flowing energy which can become attached to objects and activities which differ from the natural end towards which they might have been originally adapted.

For example, auto-erotic pleasure can arise wherever the operation of an erogenous zone becomes separated from its utilitarian function within the larger biological economy. Enjoyment "splits" from the natural object such that the mouth's sucking no longer has as its object the acquisition of milk, but rather a new experience emerges where the child starts to enjoy the very repetition of the act of sucking.

We can see that certain strains of Christian theology have a consciousness of this distinction, although they view it in a very different light than does psychoanalytic theory. Roman Catholic theology in particular identifies sinful behavior on the basis of how it might de-couple certain activities from their proper or natural ends.

For instance, the Roman Catholic Church teaches that using birth control is sinful because having sex without the intention of getting pregnant violates the principles of natural law, abstracting the act of sex from its natural end in procreation.

However, psychoanalysis argues that this un-naturalness of human beings whereby their actions can "deviate" from instinctual ends constitutes one of the primary structures of being human – it's precisely the plasticity of our instincts which creates the immense range of possible human experience.

Since our drives are not so rigid as to slavishly follow the ancient biological paths carved out for them in our bodies, their unusual plasticity facilitates our power to single out and elevate certain objects in the world by extricating them from the broader kingdom of natural ends.

Conversely, this also means that human beings are something of an open-ended project – more of an answer in search of the question, if you will. These instincts which formerly furnished a clearly delineated objective which could "fill the void," so to speak, no longer supply the definitive direction they once did. There is now no longer any natural object which could satisfy the panoply of drives which the human being experiences.

Rather than being pulled by objects in our world which supposedly fill the hole inside us, the human is pushed forward by the conundrum of their desire.