The first years will kill you: the surprising cost effects of graduate program structure

Most students only look at the price tag for a graduate program, but it’s crucial to understand the difference between price and final cost. The sticker price of fees and cost per credit aren’t a reliable guide to final cost.

Most students only look at the price tag for a graduate program, but it’s crucial to understand the difference between price and final cost.

Price is what the institution charges for the education.

Final cost is what you ultimately pay for the education.

These two things can be dramatically different!

Many students don’t realize that the structure of the program which they choose can either work for or against them to push up the total amount of money which they will pay out of pocket for their education. The sticker price of fees and cost per credit aren’t a reliable guide to final cost.

A lot comes down to the magical compounding power of interest. Interest works on time, so time works against you when it comes to final cost. Interest adds up fast. The key to financing your education in a way that won't ruin your life is understanding how program structure affects interest.

For personal reasons, I was doing an analysis of three different PsyD programs — University of Indianapolis, Roberts Wesleyan University, and Xavier University — and the difference that program structure has on final cost really leapt off the spreadsheet at me. I had to share, especially because this kind of real talk could save many graduate students a lot of heartache.

Note: I don't work for or have any affiliation with the institutions mentioned here. This is my own research and analysis, and it's not intended to be either a puff piece or a hit piece on any the programs mentioned. Thanks for understanding!

U of Indy - the most expensive program

Let’s first take a look at University of Indianapolis’ PsyD program —

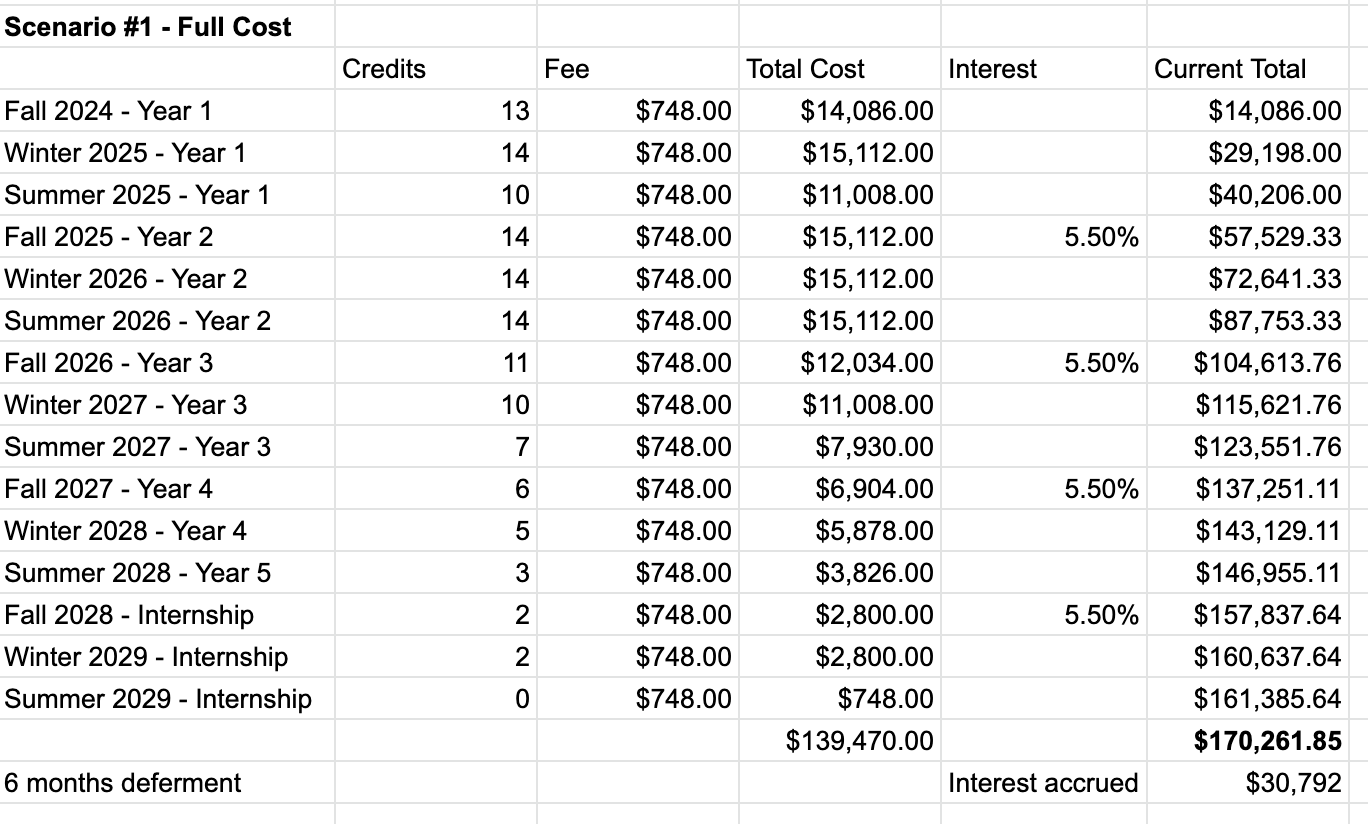

In this scenario, we assume that you pay everything using loans with a 5.5% interest rate (which is perhaps generous in our current inflationary environment), and either don’t qualify for or don’t take advantage of the university’s limited assistantships. In future scenarios, we’ll factor in the assistantship to see how a few minor changes can affect (or don’t affect) the final cost.

Notice the difference between the price tag ($139,470) which is based on the price per credit ($1026) and the flat semester fee ($748), and the final loan balance accrued over the five years ($170,261.85).

Right off the bat, if you had only done the math for the program based on the price tag, you would be $30,792 short in your estimate of what the program will actually cost you, which is to say, what you will owe when you are done. This is the terrifying power of interest.

But further, notice how the structure of the program itself makes the problem of interest even worse than it needs to be — the course load is heavily weighted towards the first two years. There are a total of 125 credits to complete the program, but 70 of those credits are within the first two years of the program!

This creates a problem for the student who is using loans to finance their education. The student has taken out large sums within the first two years of the program, but now those large balances are just going to sit accruing interest for the next three years. The program structure requires the student to rack up a huge debt initially, and then lets that loan silently metastasize, waiting for the young psychologist to graduate and go into re-payment.

Let’s model that. Under this model, what would re-payment look like?

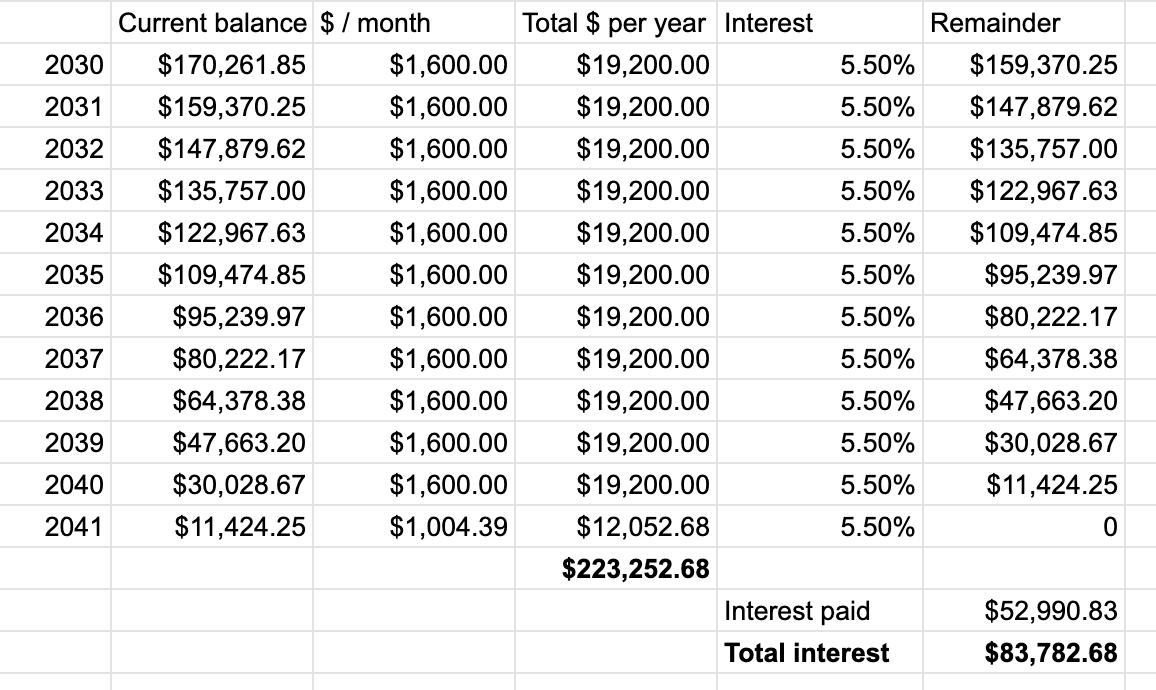

Here’s an aggressive payment plan I put together. It allows this hypothetical student to pay off their loans in 11 years. I suspect that most psychology students don’t do this though, and many will enroll in the income based repayment plan. I have a relative whose children are both in college, and she is still making payments on her PsyD which she completed before she was even married. This debt will follow you for the rest of your life if you let it.

As a side note, you do have the option to take advantage of public service loan forgiveness (PSLF), but you really have to stay on top of the details, and you also have to work in qualifying organizations for at least 10 years. This route could be fine if you want to work in non-profit hospitals, clinics, or community centers, or perhaps at universities, in prisons, or for a state or county. There are a lot of options, but you will be locked in for a decade of your life. Choose wisely.

In this scenario which I outlined above, this dedicated student pays $1,600 a month (!!!) for 11 years, only paying $1000 a month in the final year. When they complete paying off their loan, they have paid the loan servicer a total of $223,252.68!

So, a program that on paper costs $140,000, actually ends up costing the student over the course of 11 years a total of $223,000. The total interest accrued during the program amounts for $30,000, and the total interest which they pay by the end of the loan adds up to $84,000.

This is wild stuff. Not only is this program expensive, but the cost effects of financing the program ends up costing the student $84,000 in interest, and that’s when we use a pretty aggressive re-payment plan.

In this model, the student is paying nearly $20,000 a year towards their loans. Assuming that the student can land a job in their field, they can probably reasonably make $75k-$90k a year. This would put them at about 1/4 their yearly salary just going towards loans. They could pay more if they lived frugally, and they could pay even more if their household was dual income, but that’s an absolutely grueling slog. And, of course, kids would be out of the question.

Alternative scenario - Assistantship

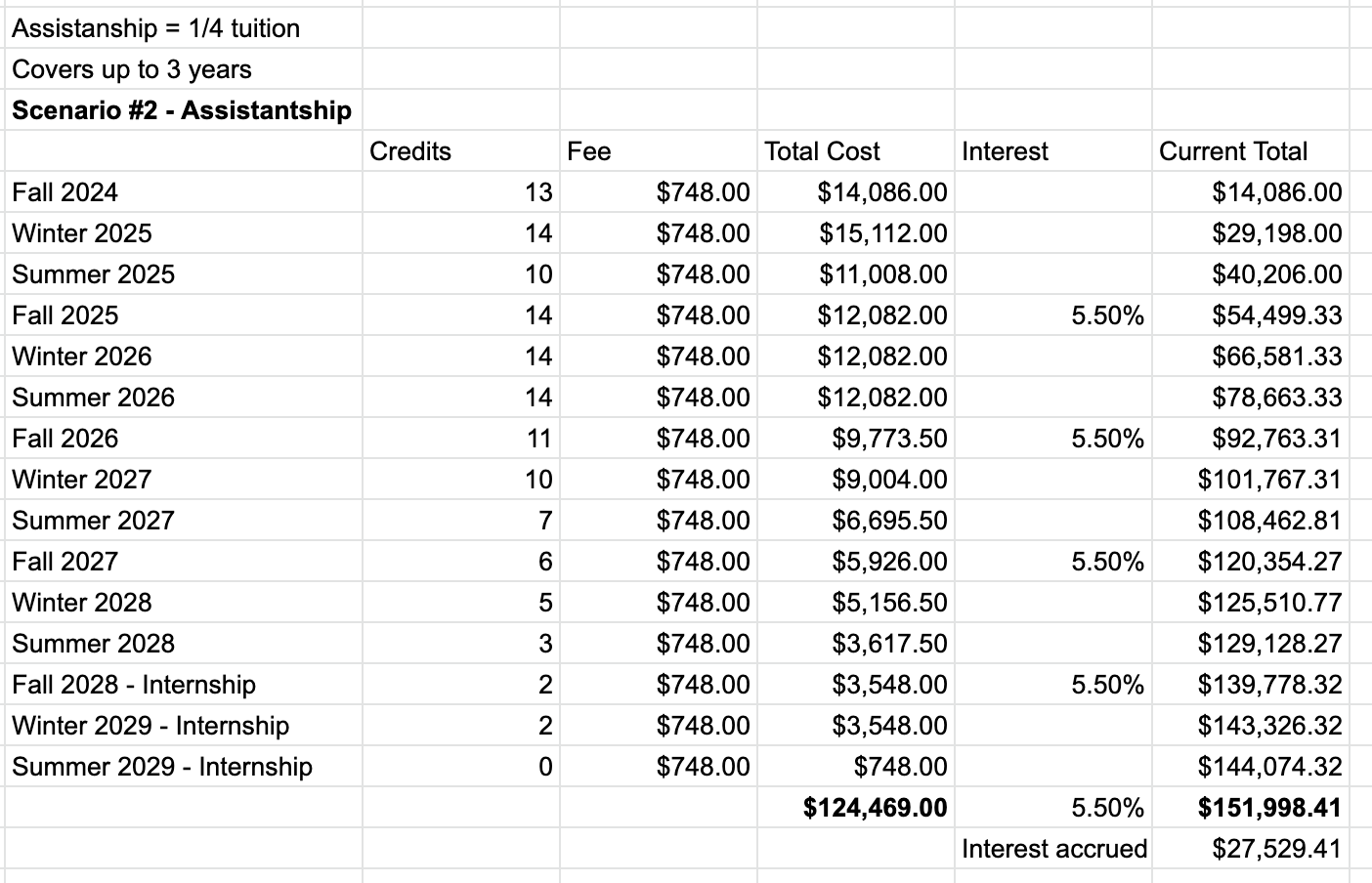

The University of Indianapolis’ website indicates that they offer students a limited number of assistantships, which reduce tuition by 25% over 3 years. The student has to display outstanding undergraduate or graduate achievement to qualify, and then to keep receiving it they must stay enrolled full-time, have good academic standing, and put in about 7 hours of work a week.

Let’s model how that assistantship would impact this student’s final costs. In the model below, I apply the 25% tuition reduction to years 2 through 4, under the (I think, reasonable) assumption that one likely won’t secure the assistantship in their first year, for a variety of different reasons.

Here is where we see how much weaker the correlation between price per credit and program cost actually is compared to our prior expectations — a simple-minded assessment would think that a 1/4 reduction in tuition for 3 of the 5 years of the program would amount make a substantial dent in the cost, but it actually doesn’t have much of an effect, as the numbers above demonstrate.

The student’s overall cost only sees about a $15,000 reduction, although the the total loan balance accrued is only ~$19,000 less than the original scenario. Interestingly enough, the interest accrued is almost comparable to the first scenario as well, displaying only about a $3,000 difference.

In this scenario, the tuition cut didn’t touch the flat semester fee, and it also only reduced tuition on years 2 through 4 in which years 3 and 4 had a lower credit load. I think this contributes to the assistantship having a lower effect than one might expect.

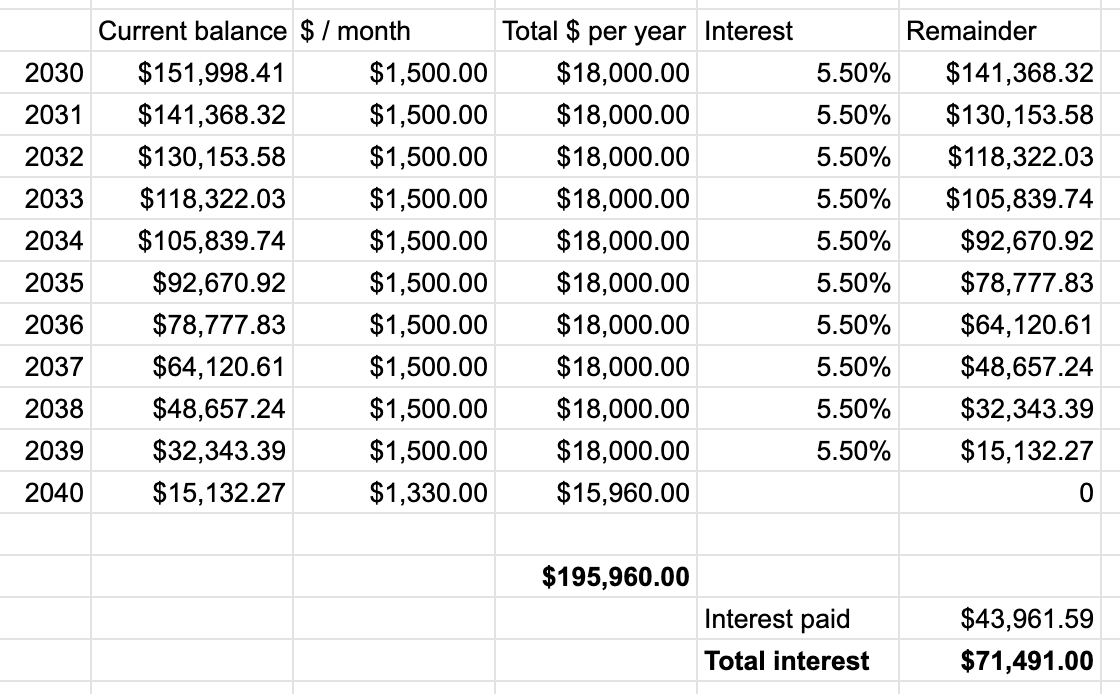

The effect on re-payment is noticeable, but not substantial.

These assistantships are limited, and the website says that they take about 7 hours a week. It’s almost not worth it, when you do the math though. You might be better off finding a part-time job instead (although I haven't done that math yet). A 25% reduction in tuition over years 2 through 4 seems to have an effect of reducing the student’s overall final cost by about $28,000, with about $13,000 of that being a reduction in the final amount of interest which the student pays. Only about $17,000 of that seems to originate from actual reduction in the original cost of the schooling.

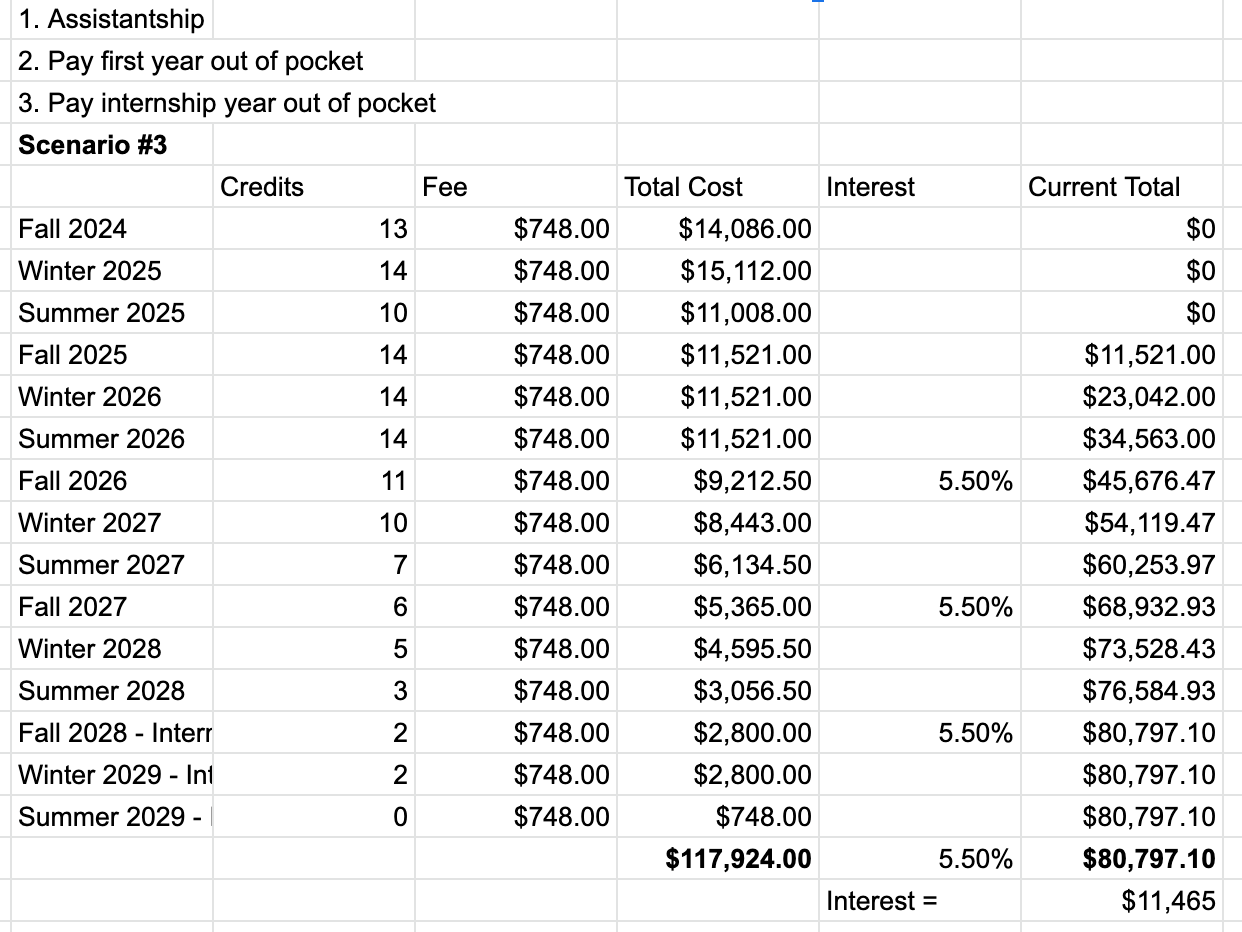

Alternate scenario - How I would try to finance this program

After I noticed what was happening in both of these scenarios, I brainstormed a plan for how I would approach financing this program if I were going to be attending as a student.

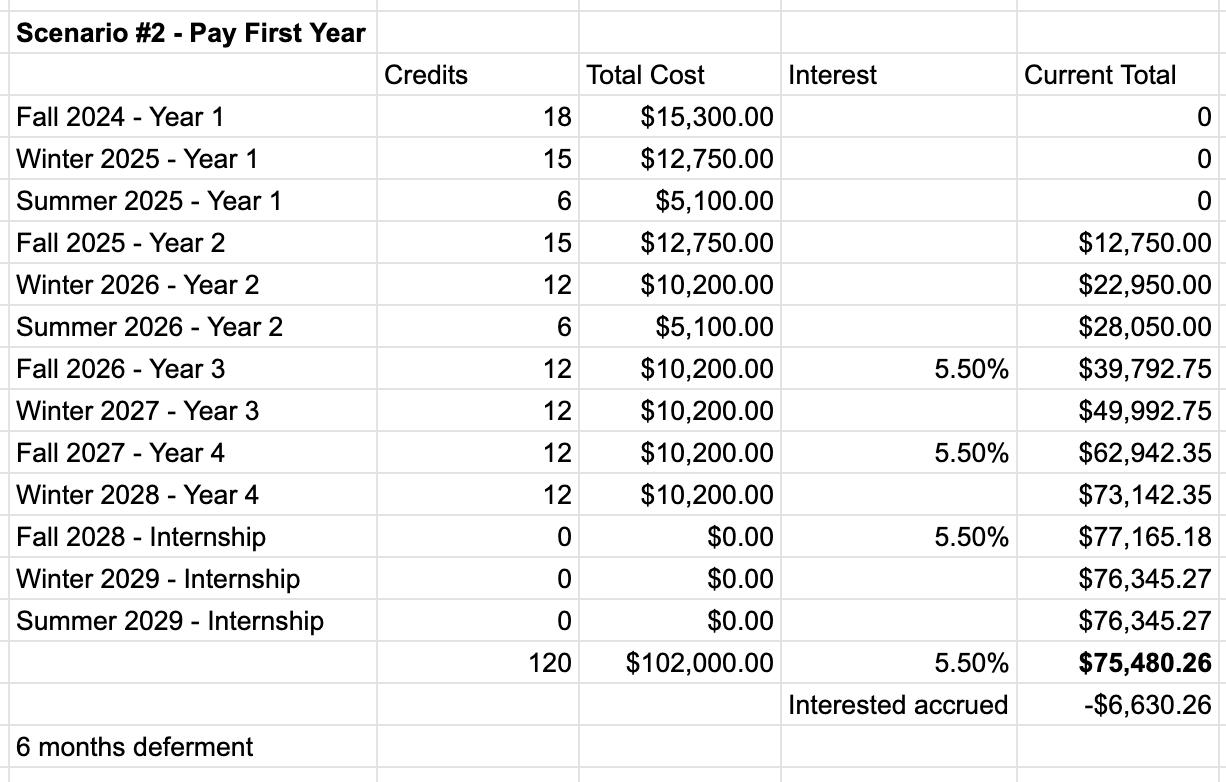

First, since I noticed that the first year was the heaviest load of credits, I decided that I would save up ahead of the program in order to pay the first year out of pocket, thus eliminating the need for loans in the first year.

Next, I would take advantage of the assistantship in years 2 through 4. Since it’s available through the school, and it’s not nothing, I thought I’d incorporate that into my plan too. It would be interesting to model how this effort/reward compares to just working a part-time job, but that would also require modeling a household budget, which I didn’t want dive into just yet.

Lastly, I realized that the final year of the program was an internship year where I would actually be drawing a wage at my (hopefully!) APA accredited internship. Since I’d just be paying a couple credits and the mandatory registration fee, I should just pay those out of pocket, instead of adding them to my balance.

So, if I (1) pay the first year out of pocket, (2) use the assistantship, and (3) pay for the final year’s fees from my internship salary, where does that get me?

Here’s what we see — The total amount paid is $22,000 less than the un-discounted sticker price (a 25% reduction), but the total interest accrued is cut by 2/3 (saving me ~$20,000 in interest accrued while I’m in school). Further, the overall loan amount which I have accrued by the end of the program is almost $90,000 lower than the first scenario, and $70,000 lower than the scenario where I just take advantage of the assistantship.

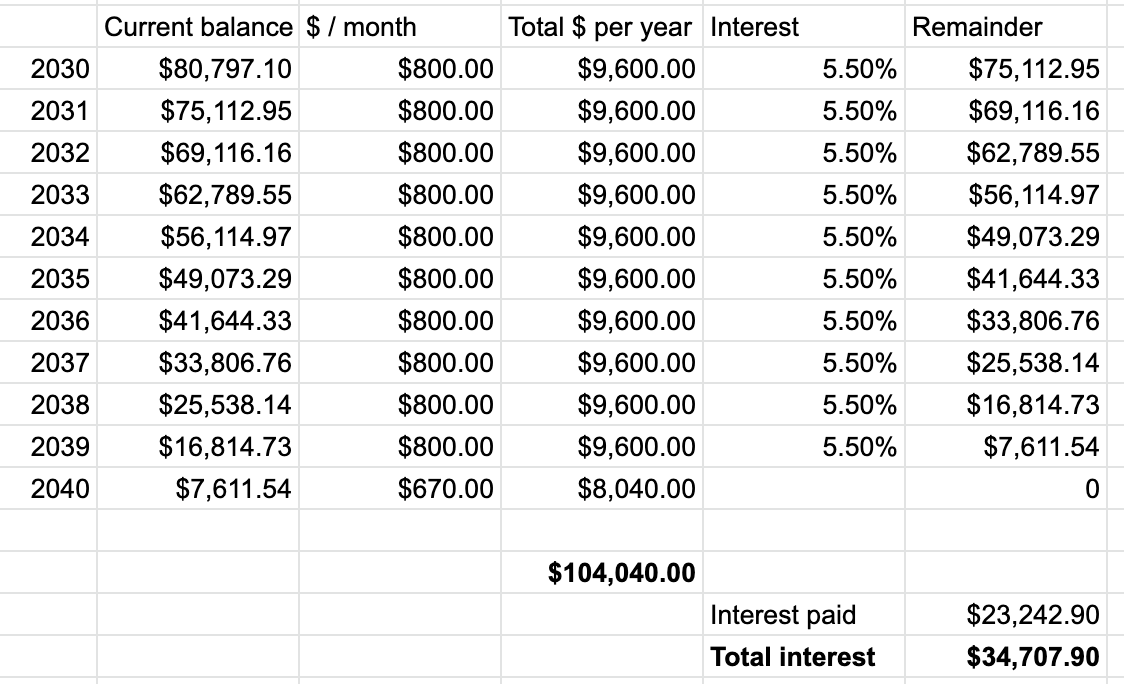

The differences extend into the re-payment period as well.

In the end, I only pay $104,040.00 for this program if I pay the loan off in 10 years. I end up paying $35,000 in interest, as opposed to $84,000 and $71,000 in the other scenarios respectively.

Compared to the first scenario, the final cost of the loan is less than half (about a $120,000 reduction). This means that by simply by paying $46,000 out of pocket, primarily to cover the first year, and taking advantage of the assistantship, I reduced my final cost by more than $70,000. This means that I can make a monthly payment of $800, which is half of what I would have had to pay in the original un-discounted scenario.

When I did this math, I was blown away. The power of interest truly is terrifying, and the graduate student absolutely has to take this into account before they embark on their journey.

But this is just one program. How does U of Indy’s program structure and costs compare to other APA accredited PsyD programs?

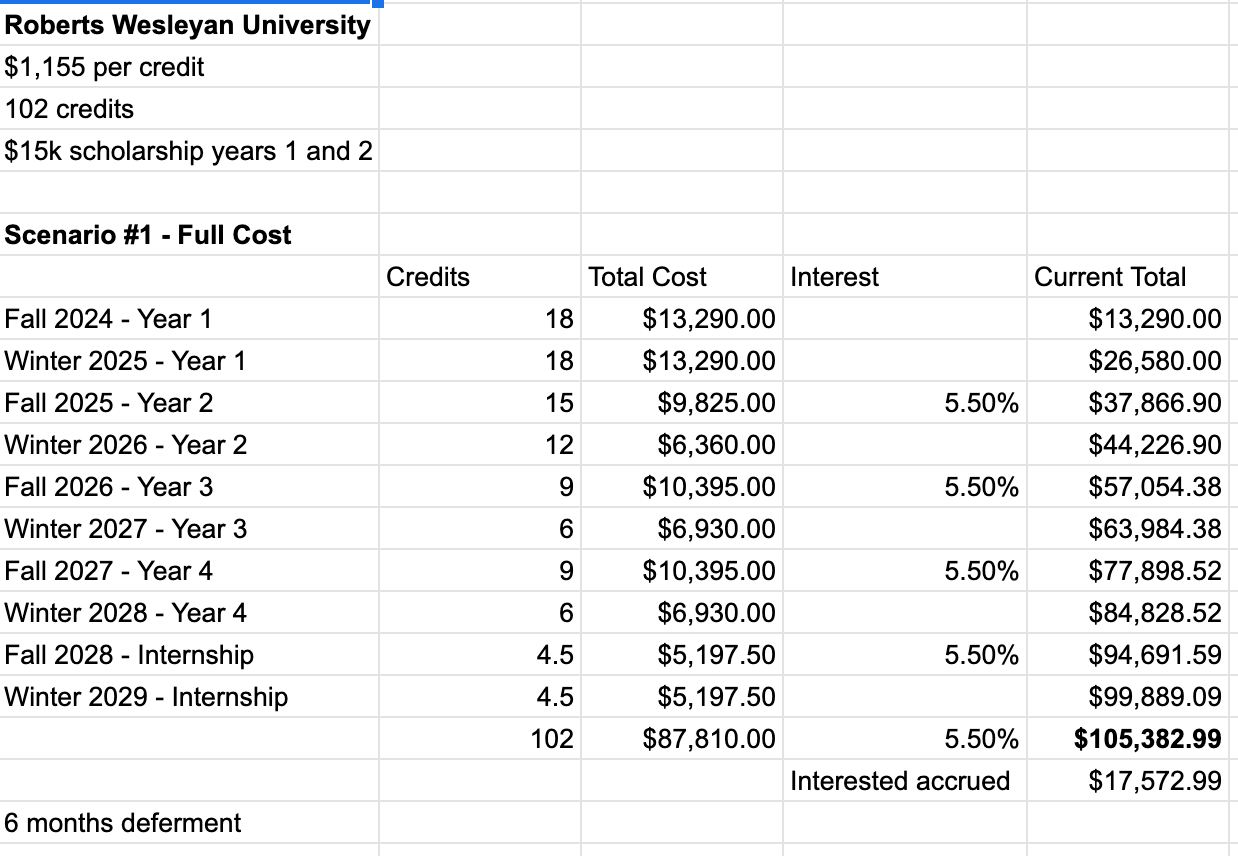

Roberts Wesleyan University - targeted aid

Next we’ll take a look at Roberts Wesleyan University, primarily because they offer an interesting scholarship. Their website for their PsyD program claims that every accepted student automatically receives a scholarship of $30,000 spread out over the first two years.

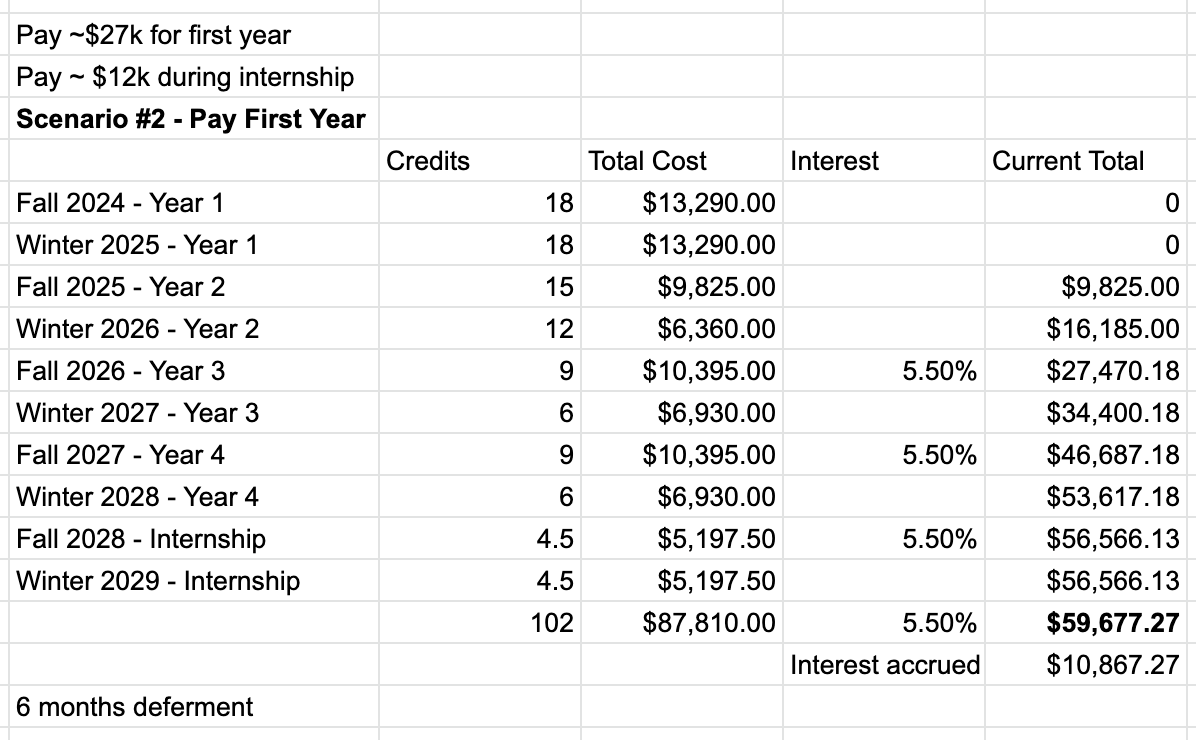

Roberts Wesleyan University actually has a higher cost per credit hour than University of Indianapolis ($1155), and they require a total of 102 credits, but it turns out being the most affordable of the three programs which I analyze here.

The reason is this — once you do the math, the scholarship they offer is much more impactful for the student than it initially appears.

Targeting the scholarship to the first two years of the program ends up being extremely helpful for the student, because the first two years are the most heavy in terms of credits. So, not only does this save the student on tuition, but they also avoid the interest which would have accrued on that $30,000 of tuition for 3-4 years.

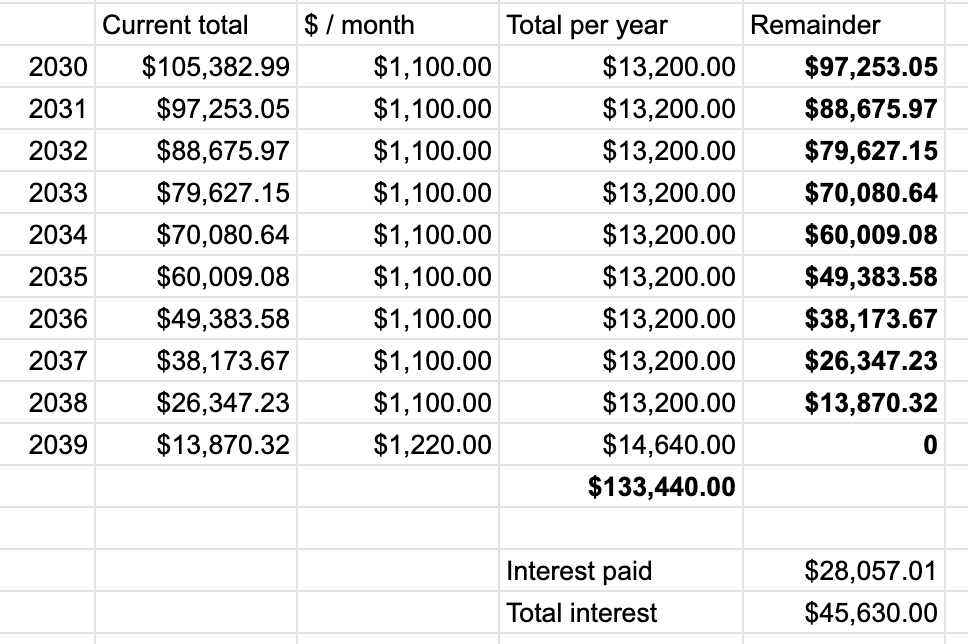

Despite having a higher cost per credit, Roberts Wesleyan University ends up costing less because they offer a targeted scholarship, and don’t have the mandatory flat semester registration fee. By the end of the 5 year program, the student has accrued $105,000, and only ~$18,000 of this is interest on the principal.

To pay this off in 9 years, a student could pay $1,100 a month, and only end up paying $45,630 in interest total. This is without implementing any of the strategies which I devised in my third scenario in which I attempted to reduce the University of Indianapolis costs.

What happens if we implement those strategies here?

If we pay for the first year out of pocket (~$27,000 instead of U of Indy’s $40,000), we don’t start accruing interest under the end of the second year, and we ultimately end up with a loan amount of $60,000 at graduation, $11,000 of which is interest.

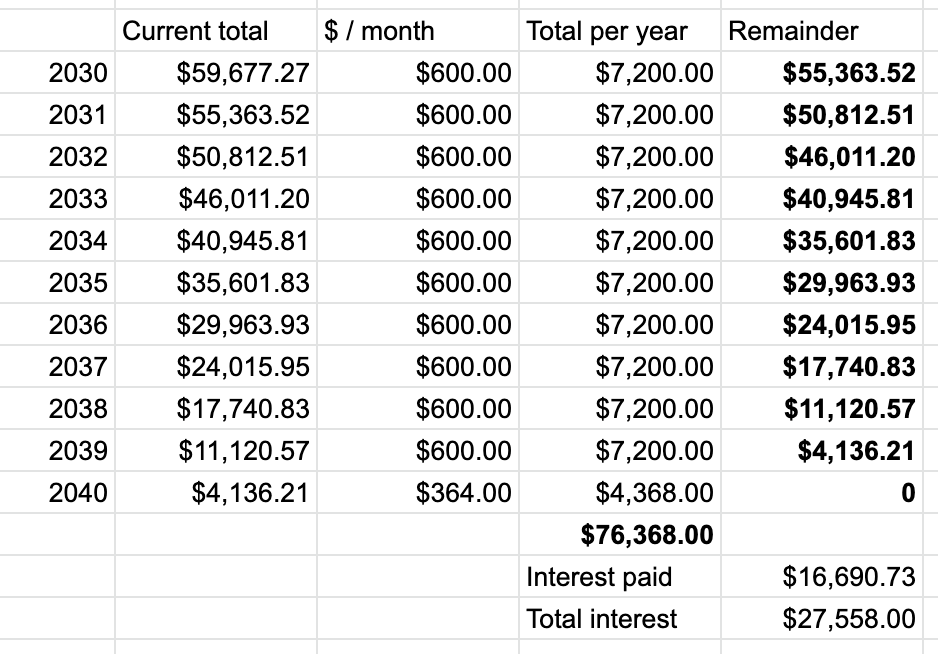

If we put ourselves on the 10 year re-payment plan, we only have to pay $600 a month for 9 years and $364 a month for the final year, putting us at a total cost of $76,368 for the whole degree, with $28,000 of that being from the interest.

I haven’t analyzed every program, but of the programs which I wouldn't consider funded, Roberts Wesleyan University is the best deal that I’ve found thus far. From what I understand, Baylor, Rutgers, Georgia Southern, and Indiana State are mostly or completely funded programs, so those are all worth looking at, but Roberts Wesleyan University seems to have structured their program in a way that makes life easier for their graduates (whether they realize it or not!).

Also, I do need to note that I haven’t factored in the cost differences of living in Rochester NY (where Roberts Wesleyan University is located) versus living in Indianapolis, IN. It may very well be the case that the cost of living differences wipes out some or all of the cost difference, but I suspect it depends on how you structure your lifestyle.

Xavier University - even structure, even costs

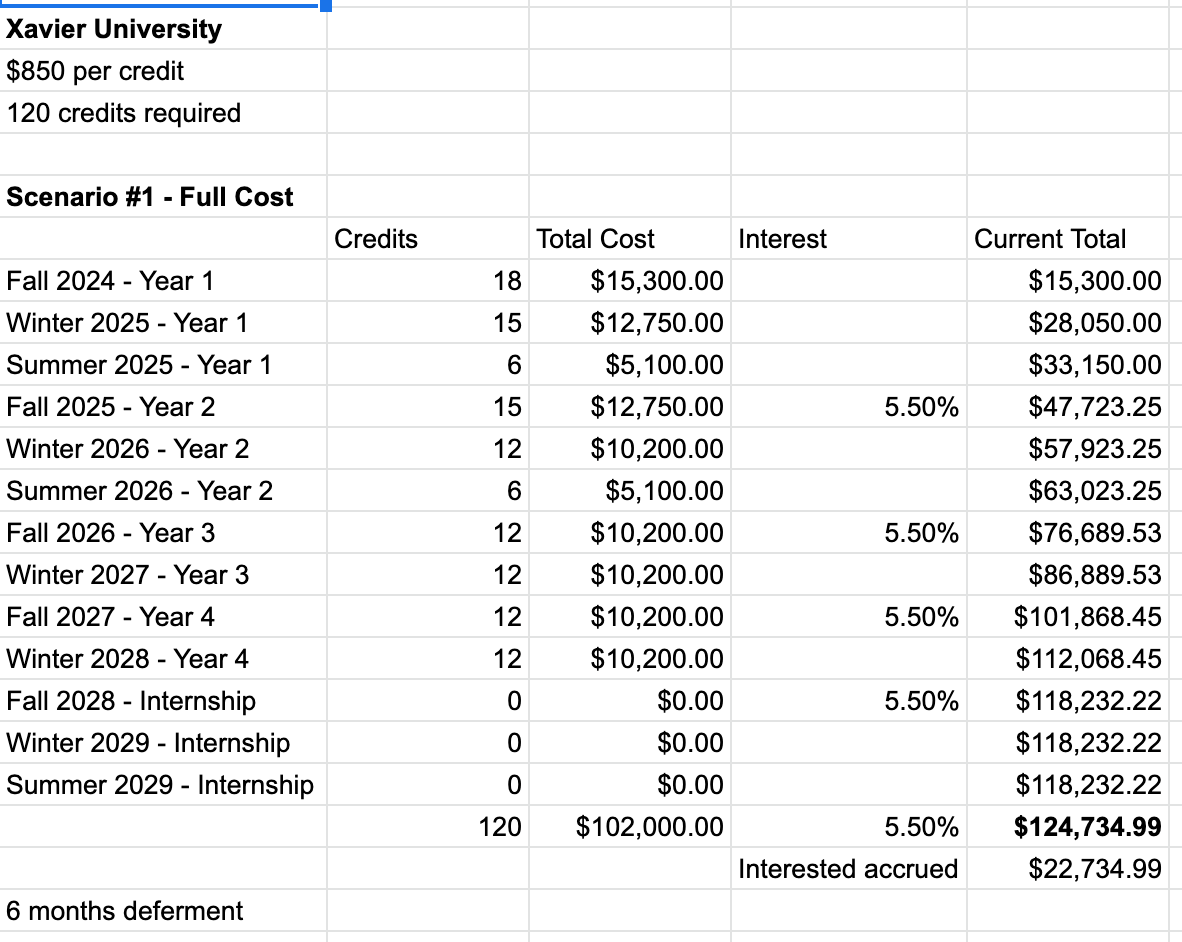

As a bonus, I want to briefly include my analysis of Xavier University's PsyD program, a Jesuit university in Cincinnati, which provides our third and final example. Xavier’s program exemplifies a simplicity and steadiness of cost structure which maximizes the student’s ability to manage the growth of their debt.

They don’t offer any specific scholarships from what I can tell on their website, but they do have one of the cheapest cost per credit hours which I’ve seen, and they don’t charge a mandatory flat semester registration fee like other programs. This means that the student's final internship year basically doesn’t cost (as best I can tell from digging around on their website’s program curriculum and fee structures).

The thing I find impactful about Xavier’s program structure is the more consistent way that the credits are distributed across the program.

You don’t see any fall or winter semesters where the student is taking 6 or 9 credits. Instead, you see 12’s and 15’s mostly across the board. While this means that every semester is consistently high, the cost is spread more evenly so interest is not snowballing on you quite so dramatically. Plus, Xavier’s cost per credit hour is also the cheapest I’ve seen in my research.

Take look below at what re-payment would look like for Xavier’s program —

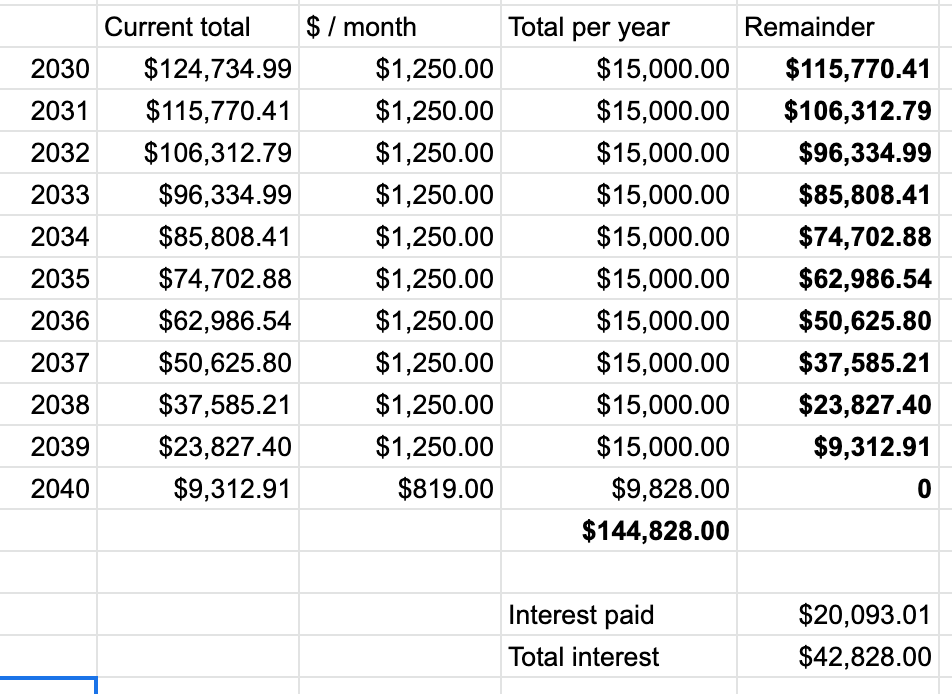

Overall, if you purely finance your education through debt, this student would pay $145,000 in the final analysis, if they paid off their loans in 10 years. They would end up paying $42,000 in interest beyond just the sticker price of the program.

Briefly, let’s take a look at what happens if we implement some cost saving strategies —

Alternative scenario

You’ll notice something weird in the picture below — the interest accrued is negative. In this analysis, I decided to add in a new strategy. Since the final internship year is functionally free, and the student would be drawing a full time salary during their internship year, why not start making payments on your loans during the final year?

Notice that a monthly payment of $400 starting in 2028 and continuing through the end of 2029 effectively wipes out and even exceeds the effect of the interest which accrued over the previous 3 years.

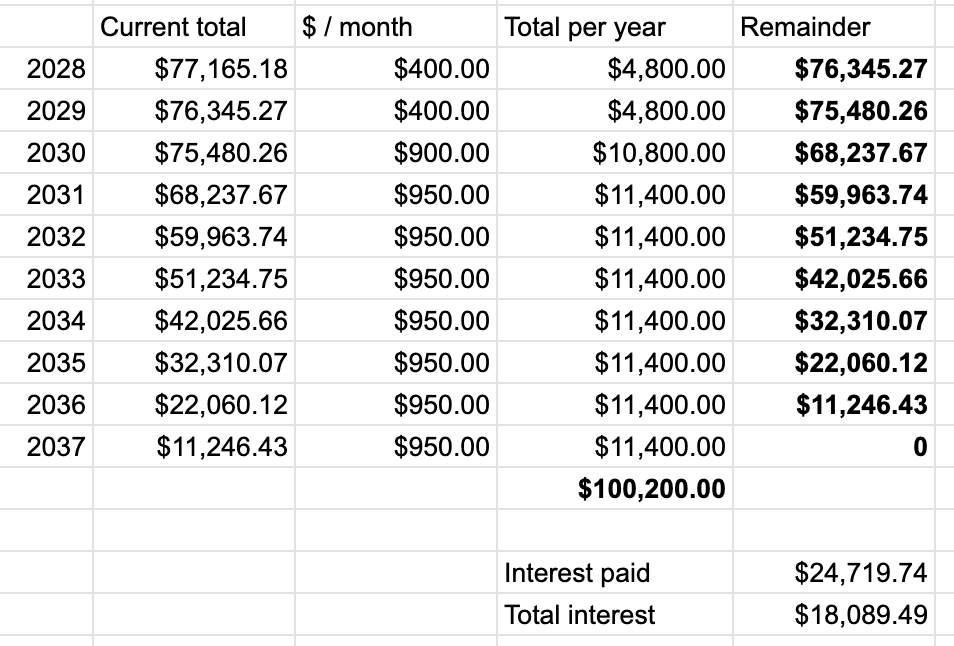

So, if we pay for the first year (the most expensive year) out of pocket (~$33,000) and we start making a $400 a month payment on the loan starting at the end of year 4 through the end of the internship, we end up with an accrued loan balance of $75,480 when we graduate, and we’ve effectively paid for more than the interest which we accrued.

When it comes time for re-payment, the student could pay less than $1000 a month to knock the loan out in the 8 years following graduation, paying a total of $100,000 for the entire degree, with $24,719 of that being the interest accrued over the 8 years of re-payment.

Conclusion

If you skipped down to read the whole analysis, I’d summarize the key takeaways like this —

The structure of a graduate program has a dramatic effect on the final cost which the student ends up paying. The sticker price is not always an accurate guide! I found that the program with the most expensive price per credit ended up being the cheapest program, and the program with the cheapest price per credit ended up being the second most affordable of the three.

The structural program factors which play into final cost are numerous, including things like mandatory semester registration fees, the timing and size of scholarships or assistantships, and the distribution of credits per semester across the entire program.

By far the most important structural factor is how much interest is working against the student. When a program is structured in such a way that students are acquiring more costs earlier on in the program, or if assistantships don't affect large flat ancillary fees, then the student ends up in a situation where they have large sums accruing interest, and later discounts on tuition aren't as impactful because they aren't taking fewer credits later on in the program.

Programs can increase their equity, affordability, and impact by designing programs which shield students from the impact of interest. I've already pointed out that programs can focus on constructing their programs in ways where the credit loads are more evenly distributed across the entire program, but they can also consider reducing or eliminating administrative fees. There may be more ways to get creative with this, but that's where I would start.

Programs can target their aid in ways that make the money even more impactful students. Like how Roberts Wesleyan University's scholarships targets the first two years of the program which are the most expensive, this massively increases the impact of that scholarship. If a program were front loaded, that type of scholarship could offset things for students, rather than providing assistantships which just provide tuition reduction across all the years.

Summary of strategies to counter-attack these cost effects

Over the course of the analysis, I brainstormed a number of strategies which a student could implement to reduce the final cost of their graduate program --

- Pay for the first year (or two!) out of pocket — these are often the most expensive years, and they accrue interest the longest too, so if you can pay one or both out of pocket, you’ll save yourself a lot of interest in the long run.

- Find scholarships/assistantships which target the first couple years of the program — this gets at the same principle as the first strategy. Find ways to target the costs associated with the first and second years, because these will be the ones that kill you in the long run.

- Find a program which doesn’t drastically front load credits in the first two years — If you can find a program that spreads out credits more evenly over the course of the program, you can make sure that those first couple years don’t hurt quite as bad, and don’t accrue as much interest.

- Start paying down your loan during your final year internship — If you can either pay for your last internship year out of pocket or even start making payments on your loan during that year, you can wipe out and start to reverse the effects of interest before your loans go into re-payment after you graduate.

- Make payments on the interest while you’re in school — I didn’t talk about this explicitly, but if you have room in your budget to make payments on your loans while you’re still in the program, you should do that. At the very least, you can keep the effects of interest at bay.

Thanks for taking the time to read my analysis! While this deviates from my normal content focusing on philosophy, psychoanalysis, and theology, this does capture a core interest of mine – analyzing and building effective processes for achieving worthwhile institutional aims.

If you are a graduate student, I hope that this helped you think through how to approach planning for your future in a responsible manner.

If you are an educator, I hope that this opened your eyes to the way that your program’s structure may be helping or harming students, and perhaps you have the opportunity to impact your students even more than you are already are.