Theosis, mediate and immediate

Do we take Christ as the blueprint for God's plan for each human, or as the anomalous intersection of God and man? What theological implications does this choice have?

I was very nearly accused of monothelitism the other day (I think it was a first for me!).

I was told by my interlocutor that I had to accept that human nature constitutively possesses two wills — “the natural” and “the nomic” (is anyone aware of where this distinction comes from?) — on pain of confessing that Christ has only one will.

This move struck me as odd, because I’ve always taken the person of Christ to be anomalous, not a model for the human as such. The hypostatic union is a singularity, no?

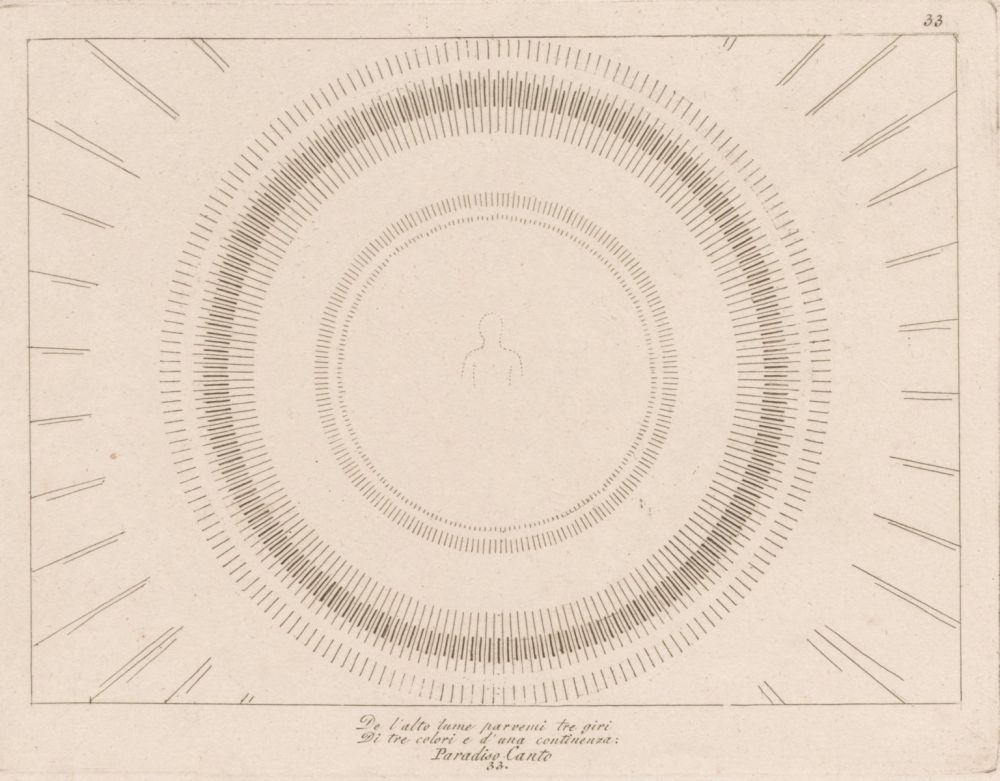

For those who care for such distinctions, the Church generally professes a doctrine of dyothelitism concerning Christ, a view exemplified by St. Maximus the Confessor and affirmed at the Third Council of Constantinople, in which the one person Jesus Christ possesses both a human and a divine will.

(No one asked me, but personally, I think such a formulation is a category mistake — a nature is not the sort of metaphysical entity to possess a will! Does that make me a monothelite…?)

Operating with this understanding of persons and natures, we would say that Christ has two wills precisely because he has two natures, and that since I am not a hypostatic union of a human and divine nature — I am simply a human — I am not analogous to Christ’s metaphysical constitution. It has never occurred to me that one might generalize the schema of Christ’s persons and natures to a normative construction of humanity as a whole.

However, my interlocutor thought otherwise, and he insisted on each human possessing two wills, arguing on the basis of the Eastern Orthodox doctrine of theosis — God’s mission in Christ to humanity is to transform human beings to make them like Himself, to raise the human up to the divine.

Under this framework, one must take Christ as the blueprint for God’s plan for each human, rather than as the anomalous intersection of God and man. The end of man is to possess both a human and a divine will within.

This dispute draws out some illuminating contrasts between competing eschatological visions in the Christian Church. In what sense is God uniting creation to Himself? In what way do we human beings become like God in Christ? If we are made like God through our union with Christ, is this union with Christ the same or different as God’s union with His human nature in Christ?

How do we understand St. Athanasius’ famous dictum that “God became man in order that man might become God?”

Whatever Athanasius means, I see good reason both from Scripture and from reason to think that whatever the nature of our union with God in Christ is, it differs in some important respect from the union which God enjoys with Himself through His incarnation.

An example — Christ is the son of God by birthright, whereas we are children of God by adoption. Paul makes this distinction clear enough in his writings. In adoption, what would normally have been secured by nature is simulated or constructed through a legal mechanism — a girl who was not created by my seed may enjoy all the rights and benefits for being my daughter after I adopt her. This is a beautiful and joyous thing.

However, I can never be a son of God who was eternally begotten from the Father. That path is closed to me, just as an adopted daughter could never be a daughter begotten from me. We cannot change our nature in this respect. Jesus’ status as ‘eternally begotten’ cannot be shared with any creature, not even with his own human nature (for it thereby would no longer be human).

However, the wonderful news of the Gospel tells me that God unites me to Himself by way of adoption, meaning that I get to enjoy all the rights and benefits which He confers on His own son, Jesus Christ, my faithful older brother who did our Father’s will on my behalf to secure for me a place in the family and the family’s royal inheritance. That’s a glorious thing, but it still entails that my relationship to the Father is qualitatively different in some irreducible sense from the one which Jesus Christ the Son has with the Father.

Let us consider this question from the other direction — does the indwelling of the Holy Spirit which God promises to believers secure the same level of unity with the divine which the person of Jesus Christ enjoys between his two natures?

I have never asked this question until exactly this moment, and my instinct is to say ‘no.’

Why is that?

What is different about Christ’s union of two natures in one person and the indwelling of the Holy Spirit in my person?

My initial response would be that there are still two persons in the case of my ontological arrangement, whereas Christ’s hypostatic union produces a singular person. I don’t see any warrant in Scripture to say that the Holy Spirit poured out upon me unites me to God such that God and I become the same person.

In situations like this, it can be mighty tempting to resort to the vagaries of “participation,” that old Platonic hand wave. We “participate” in God’s life, but always in a way most appropriate to our constitution as finite beings.

This formulation includes a lot of what I want to maintain, namely, that our existence as finite creatures possesses some mode of relation to the divine which we enjoy through God’s grace, and which does not destroy our creatureliness, but precisely affirms it in the act of elevating it to enjoy a communion with the life of the Trinity.

Something of this is affirmed in the notion of the ‘natural’ and ‘supernatural’ ends of man, an idea which many of magisterial Reformers nonetheless took with them from the Catholic Church.

Scripture seems to indicate that the original end of man oriented towards “being fruitful, multiplying, and filling the earth, taking dominion over it” had lurking behind it a higher — “super-natural” — end which could only find its fulfillment in God. In short, creation never existed simply for its own sake, even if God did make it with its own set of internal goods.

Because of the way that this two-fold schema testifies to the original goodness and integrity of creation, I’m at pains to maintain that the creature who becomes God through theosis does not stop being a creature, even if they are a glorified creature in the sense which St. Paul’s tries to gesture at in 1 Corinthians 15. The creature becomes more fully itself through its union with God, and this seems both different and more fruitful than professing theosis, as I understand it.

The creature’s participation in God seems to always remain slightly different from Christ’s own participation in God, for Christ can be addressed and worshiped as God directly, whereas we cannot be accorded that same honor without committing blasphemy. Scripture therefore seems to maintain that a qualitative difference remains even after our union with Christ in God such that Christ nonetheless still enjoys some preeminence.

What do we make of the Adam and Christ comparisons then, which my interlocutor also raised in the course of our conversation?

St. Paul’s formulations in which he juxtaposes Adam and Christ, and which St. Irenaeus famously picks up, seem to model a way of understanding the symmetry between God's work of creation and His work of redemption.

Yet, there also seems to be a difference between our relation to God and Adam’s relation to God, especially in his being a son of God by generation — He received God’s breath, and he did not have a human father — ultimately making him a federal head or covenantal representative of all human beings.

Here we hit on something — the covenantal representative must be anomalous in some sense. The federal head differs from the one who is represented if only in the sense that the one relates to God directly and one relates to God through the representation of another. The federal head represents themselves immediately, whereas the represented one is necessarily mediated.

Our relation to God, even in our unity with Him, must always remain circuited through Christ as our covenantal representative in whom we are united to God.

Therefore, we must say that Christ is united to God immediately, and we are united to Him mediately. This mediation or refraction is never obliterated, even in the glories of the resurrection and the jubilation of the new heavens and new earth, for God never ceases to uphold the creatureliness of the creatures He has made.

To confess that we are united to God according to the same blueprint as Christ is to ignore the dialectical movement which took place in order to make that unification possible, for the dialectical path of our mediation through Christ fundamentally changes the nature of the unity which we enjoy with the Godhead.

Thus, the doctrine of theosis insufficiently theorizes the detour through the Incarnation, both for us and for God too, and lacks an articulation of the power of mediation to transform the relation of unity between God and man.

We arrive once again at the contest between Plato and Hegel, in which Hegel thinks in a more properly cruciform manner which willingly undergoes the passage through mediation. Hegel thus embodies the most potent and radical tendencies of Protestant thought, and leads us to confront the full logic of the cross in the most brutally naked way possible.

In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, as it was in the beginning, is now, and forever shall be — Amen.