Oedipus in a Biopolitical world (Part 2)

With the emergence of the biopolitical state, death no longer appears as the point of power’s absolute exercise, but rather as the appearance of its mysterious failure.

This essay comprises part two of a three part series on the question of psychoanalysis' place within our contemporary biopolitical society. You may find part one here.

What is biopolitics?

Last week I introduced our theme for this brief series — what place can Oedipus have in our biopolitical world? In a time in which power everywhere enjoins us to speak our desires, what revolutionary potential can psychotherapy hold for us?

Increasingly, the medical professional serves as the priest of our time — diagnosing our deepest suffering, while also prescribing the practices which will lead to our absolution. Even in our heart of hearts, we find that the watchful eye of power is there with us, nodding or shaking its head in the visage of the therapist.

Can the psychoanalyst avoid becoming caught in this clever web whereby power infiltrates even our most internal experiences of ourselves? This Foucauldian criticism of psychoanalysis draws our attention to the biopolitical context in which psychoanalysis is practiced. Therefore, to provide an answer to Foucault, we must first clarify what he means by his concept of “biopolitics.”

From the Repressive Sovereign to the Biopolitical State

I have chosen in this particular piece to draw on the concluding chapter of Foucault’s History of Sexuality, Volume 1 in which he outlines a historical transition of power’s operation from that of “the right of death” to “the power of life.” Focusing on this portion of text was a tactical decision on my part, and should not be considered exhaustive of what could be said on the topic.

In this transformation from power's exercise in what he calls a "right of death" to the "power over life," Foucault sketches for us a political move from “the sovereign” to “biopower” in which power no longer lords over the boundaries of life and death, but now actively seeks to inculcate in the populace a reduction of death and an increase of life. In biopolitics, power comes to concern itself with the maximization and technical optimization of life itself.

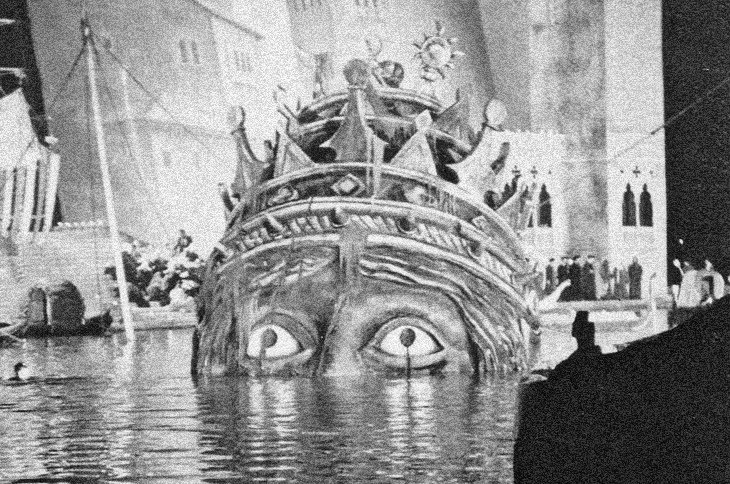

Foucault explains that, prior to roughly the seventeenth century in the West, sovereign power operated according to a model of “the right of death” where the sovereign exercised power primarily in the decision whether to kill or let live. Under this power dynamic, the king was the source of the right to torture or execute, and also displayed his sovereignty through the exercise of clemency.

Political discourse exhibited this dynamic through a fixation on the king’s body, and concerned itself with the bodies of the subjects only insofar as their actions constituted a direct threat to the king’s body. His body was considered not simply his person proper, but also his authority and his kingdom, as they were understood to constitute an extension of his body.

The status of the sovereign was intimately connected to the right to commit violence without impunity. The sovereign acted upon the bodies of subjects through the application of brute force or through the deprivation of their property (family included), and power was experienced as the ruler’s absolute right and unparalleled ability to perpetrate this violence against subjects.

Foucault therefore describes this sovereignty model of power as “deductive” because it operates primarily as that which curtails, deprives, and overrules.

However, Foucault subsequently describes the emergence of a new form of power which focuses on the body of the subject rather than the body of the king. This power concerns itself not with choosing between life or death, but with cultivating, guiding, and increasing the forces of life within the citizen’s body (the individual) and the body of the citizens (the population). In this way, power becomes additive or multiplicative, rather than deductive.

This new biopolitical orientation which operates according to a “power over life” makes all of life its domain of control by putting human actions under the microscope to understand their mechanics – life as a petri dish and society as a laboratory for ongoing experiments.

Do not kill the criminal, but rather confine him, compel him to speak about his experience, and learn how to change him. In a biopolitical society, punishment becomes reform, and discipline becomes rehabilitation. Confession no longer serves to establish the justice of the punishment, but rather to unearth the social forces operating within the event of this individual's deviation from the norm.

Instead of a repressive sovereign who pursues extraction through violence, power now aligns its mechanisms towards the measurement and generation of abundance. Death does not represent power's domain of absolute dominance, as it once did for the king, but rather all the manifestations of death in a society (famine, disease, violence, etc...) have become the problem which power now devotes itself to "solving."

With the emergence of the biopolitical state, death no longer appears as the point of power’s absolute exercise, but rather as the appearance of its mysterious failure.

Biopower's invisible operation

Foucault's work takes particular interest in the different stances these two forms of power take towards the individual. Power under both frameworks needs to individuate particular objects which it can control, but “the right of death” and “the power over life” each employ different mechanisms of individuation, producing vastly different consequences.

The subject who lives under a regime where the sovereign wields the right to death experiences this power as a force intruding from the outside. The sovereign exerts a radical negativity on the subject, forcing them into submission through instruments of fear, thereby tracing the subject’s silhouette with the application of external violence.

Under this framework, the subject’s life constitutes a domain of general activity, but power haunts the horizon with its violence, always reminding the subject of power’s arbitrary ability to strike with or without reason. This model most closely resembles the idea of repression which operates in popular narratives about what we should fear politically and what we are seeking to liberate ourselves from.

In contrast to the right over death’s radical negativity, the aim of biopower is for the biopolitical subject to not experience power's operation at all. Biopower functions as the invisible hand which imperceptibly guides the movement of the subject’s inner freedom and self-understanding through its infiltration of the most basic operations which the person takes up in their seemingly spontaneous acts of self-creation.

Unlike the king, biopower has to constantly work to erase its own presence. In true scientific fashion, the actual operations of power must become imperceptible so as to avoid the data anomalies which can be produced by an observer's entanglement with their own experiment. Biopower wants to hear "the truth of the matter," as we discussed last time, and the only way to excavate this gem is through inculcating and guiding the subject towards a desire to speak and act.

Through various technologies of the self, the biopolitical subject unites society’s web of power relations within themselves – they become both the watcher and the watched, both the manager and the employee, both the scientist and the specimen, both the patient and the therapist. A panopticon is erected in the mind.

Conclusion

Slavoj Žižek has sketched a similar shift to the one which Foucault recounts here, but he stages this transition using the figures of two different fathers – one restrictive and one permissive. This drama of the two fathers mirrors the move from the repressive sovereign to the biopolitical state.

The restrictive father imposes an external law on his children, prohibiting them from doing things, monitoring their behavior, and doling out punishment. This used to be the older model for paternal power, but the figure of the permissive father has become more prevalent recently. This permissive father says that he doesn't care what you do, as long as you're enjoying yourself. When he picks his son up from college, he teases him by asking how many girls he has bedded this semester. He positively expects his son to transgress.

Zizek contends that the permissive father is more oppressive than the restrictive father. While the restrictive father only says "thou shalt not!" the permissive father is saying "thou shalt!" When transgression is commanded, it becomes a duty, and an impossible one to fulfill at that, for who can transgress "enough?" Thus, the positive command to transgress becomes even more oppressive than the repression of a prohibition.

The biopolitical society is dominated by the the figure of the permissive father (and the consequent overbearing mother, which we shall not get into here), as it everywhere enjoins us to transgress the supposedly repressive mores which have dominated society up until this point. A biopolitical regime shackles its subjects with the command to 'Enjoy!' thereby imposing an impossible duty which they nonetheless experience as the spontaneous upswelling of their own desire.

While a prohibition remains carefully circumscribed, creating a space where the subject can define themselves through a navigation of obedience and transgression, the injunction to enjoy generates a purely positive demand without any room for the negativity of boundaries or division. Since human desire has no internal limiting functions, it rises up to infinity in a pure positive affirmation.

The pouring out of words then, both in therapy and social media exhibitionism, is a confessional labor in service of this infinite command to enjoy. We probe within ourselves to understand what our desires are, whether we are being "true" to our desires, and whether we are truly enjoying. In so doing, we carry out the work of power on its behalf, and thus perpetuate its dominance in our lives precisely through this operation which we believe will be emancipatory.

This in a nutshell is Foucault's critique of psychoanalysis and its complicity with biopower. How can Oedipus answer such a damning charge?

It's just now dawning on me the immense irony of listening to Saint Pepsi's "Enjoy yourself" on a 1 hour loop while I complete this piece... The unconscious strikes again!

Setting that aside – keep an eye out for the third and final part where we talk about the possibility which psychoanalysis holds for disrupting this biopolitical regime defined by the demand to speak and the duty to enjoy. We must ask ourselves – how do we re-introduce negativity into a biopolitical society?